Chlamydia Research Group

Chlamydia trachomatis is a highly successful pathogen of significant medical importance. The CDC estimates that 10% of women between the ages of 15 to 19 test positive for C. trachomatis and 50-70% of these infections are asymptomatic. This increases the risk of widespread transmission and untreated infections, which can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease or infertility in a significant portion of women of childbearing age.

In developing countries with limited hygiene resources, C. trachomatis is also associated with the leading cause of preventable infectious blindness. In these scenarios, Chlamydia is not sexually transmitted, rather it is transmitted between infected individuals by direct contact with infected ocular secretions or from flies coming in contact with infected then uninfected individuals.

Other Chlamydia species associated primarily with human respiratory tract infections include C. pneumoniae, a major cause of community acquired pneumonia, and C. psittaci, often acquired as a zoonotic infection from birds and manifesting as a severe pneumonia. Because of the importance of chlamydial diseases, there is a great need to identify strategies to reduce/prevent transmission and limit infections to the primary site of inoculation.

Chlamydia is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterium, which means it must grow in a host cell unlike many other bacteria that can grow on an agar-based substrate. Interestingly, Chlamydia is a developmentally regulated bacterium that alternates between functional and morphological forms called the elementary body and reticulate body.

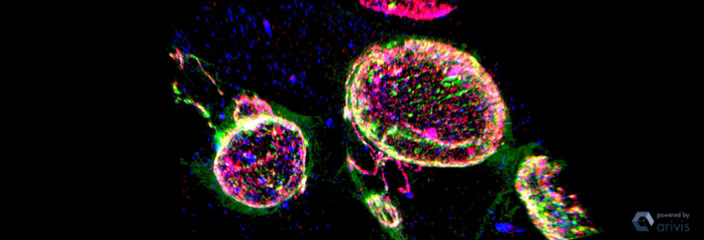

The elementary body is the infectious form that mediates attachment and entry into a susceptible host cell. The infecting elementary body remains within a vacuole that is rapidly diverted from the phagolysosomal pathway and begins differentiating into the reticulate body. The reticulate body is the non-infectious form that grows and divides within a pathogen-specified organelle termed the chlamydial inclusion. After multiple rounds of division, the reticulate body differentiates to the elementary body, which is released from the host cell to initiate a new round of infection.

In evolving to this obligate intracellular niche, chlamydia has significantly reduced its genome (~1Mbp with ~1000 genes vs E. coli with ~4.5Mbp and ~4500 genes) yet manages to perform a variety of functions that allows it to usurp the host cell in such a way as to preserve its viability.