Awake brain surgery. Feeling anxious yet?

Anxiety among patients considering deep brain stimulation surgery is common, but now UNMC innovators are using simulation and 3D printing to both screen and prepare patients for a surgery in which they remain awake.

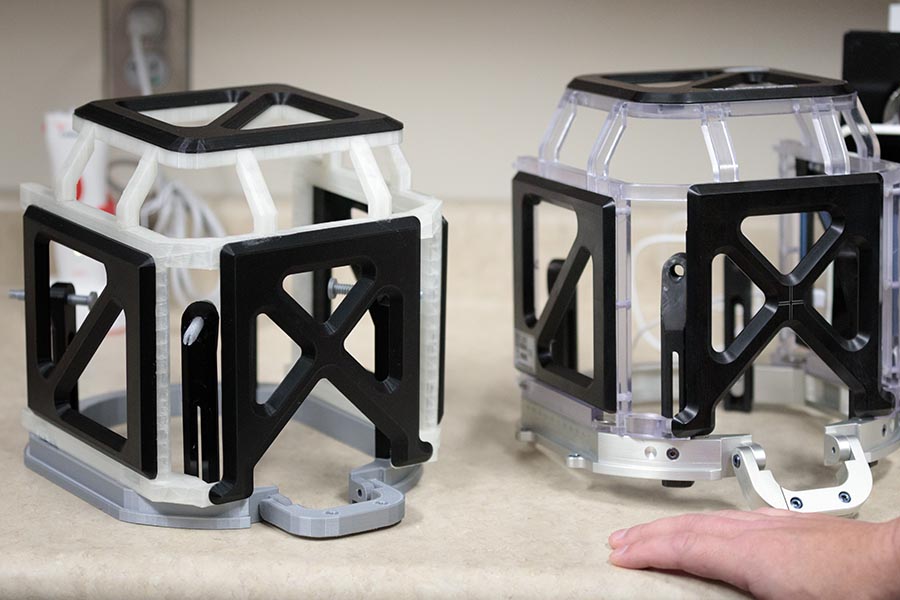

Dennis Rieke, physician assistant with the UNMC Department of Neurosurgery, models the 3D-printed stereotactic head frame.

Anxiety among patients considering deep brain stimulation surgery is so common, in fact, that the UNMC Department of Neurological Sciences has neuropsychologists on staff to screen patients to determine if they are ready for the challenging procedure and work with them to overcome their trepidation.

The procedure is used to alleviate the symptoms of diseases such as Parkinson’s, essential tremor, dystonia and other neurological conditions.

It is challenging for many reasons. Patients are awake as a hole is drilled into their heads, and they often are asked by the surgeons to respond to questions or make movements as the delicate operation, which involves implanting one or more electrodes in the brain, is underway. The procedure itself lasts three to four hours.

“They are feeling the pressure, they’re hearing the drill,” said Erica Aflagah, PhD, a neuropsychologist in the department. “At some point, there is microelectrode testing, which causes a loud, unusual noise. The surgeons are talking them through it, and they are good at that, but there are moments where a person could panic.”

“We were finding that sometimes people who were otherwise good candidates had concerns about claustrophobia and panic when dealing with the head frame and attachment.”

Erica Aflagah, PhD

Brian Maass, left, of the McGoogan Health Sciences Library’s makerspace, displays the completed replica to Dennis Rieke of the UNMC Department of Neurosurgery.

At right, Aviva Abosch, MD, PhD, chair of the UNMC Department of Neurosurgery, dons the head frame and box models with help from Brian Maass.

And for some patients, that moment arrives early – when they are fitted with a metal device known as a stereotactic head frame, which stabilizes their head during the surgery, and a plastic, box-like attachment called a fiducial localizer box, which is attached to the frame and obscures the patient’s view.

Dr. Aflagah and her colleague, Pamela May, PhD, have been told by neurosurgeons that the head frame can be anxiety-inducing for patients during the procedure.

“Part of our role is screening for anxiety that could interfere with the surgery process itself – claustrophobia, panic,” Dr. Aflagah said. “We were finding that sometimes people who were otherwise good candidates had concerns about claustrophobia and panic when dealing with the head frame and attachment.”

The concerns are understandable. The head frame is an intimidating device. Made of metal, it is screwed tightly into the outer surface of the skull for the surgery. The fiducial localizer box obscures the vision, and although that section is removed during the surgery itself, the head frame then is bolted to the operating table, immobilizing the patient’s head and neck.

It’s a tough experience for the neuropsychologists to mimic, and although they ask about claustrophobia, patients’ self-reporting is not always accurate.

“Everyone’s going to have anxiety, especially undergoing awake brain surgery, but the concern is, ‘Will they be able to respond to providers’ simple commands or to follow through the procedure?’” Dr. May said. “We wouldn’t want the anxiety to get in the way of their ability to react to the surgeon’s requests in time.”

The replica head frame, held by Brian Maass, left, of the McGoogan Health Sciences Library’s makerspace, is making a difference, said Dennis Rieke of the UNMC Department of Neurosurgery. “There’s a noticeable difference when people have gone through a procedure before as to how comfortable they are,” Rieke said. “This is a simulation, obviously, but just having a little experience goes a long way in making people feel more relaxed.”

The department of neurological sciences frequently works with the Nebraska Medicine Department of Psychology and UNMC Department of Psychiatry when dealing with patients’ pre-surgery anxieties. So Drs. May and Aflagah approached Justin Weeks, PhD, psychotherapy director of the departments’ Anxiety Subspecialty Treatment Program.

As Dr. Weeks tells it, the heart of any evidence-based treatment of anxiety is exposure, where patients face their fears. In cases where Dr. Weeks and his team have worked with patients who are considering deep-brain stimulation surgery, “we haven’t been able to have them engage in exposure” where the head frame and box are concerned, he said.

The reason? The fiducial localizer boxes are expensive – (about $30,000) – and using them for practice risks damaging them. Brainstorming with the anxiety program’s medical director, Lauren Edwards, MD, the group came up with an idea: What about a virtual reality simulation? With the iEXCEL program right down the street, would the designers and programmers there be able to create a virtual reality scenario that could mimic wearing a head frame/box device while the patient was wearing a VR headset of some kind?

The short answer, said Bill Glass, iEXCEL’s artistic director, was no.

“The problem with the VR for this type of use is, normally with VR your focal point is a short distance in front of your eyes,” Glass said. “But the head frame and box would be much closer to your face.”

Still, the iEXCEL team was intrigued by the problem. Glass wondered: What about a 3D model?

The 3D-printed replica, at left, was the result of a creative and collaborative effort by different departments and programs at UNMC, including iEXCEL, psychiatry, neurological sciences, neurosurgery and the McGoogan Health Sciences Library.

The iEXCEL team borrowed a head frame and box from the UNMC Division of Neurosurgery, and computer 3D artist Anthony Lanza meticulously photographed, measured, researched and modeled the costly pieces of equipment, working with neurosurgery physician assistant Dennis Rieke, who provided information and feedback during the process.

“The devices had multiple pieces that come apart, so I photographed them in 360 degrees,” Lanza said. “Then I loaded the photos into a 3D app as a reference and started modeling it,” he said.

“It’s very iterative. I’d get a base, and since I had the devices at my desk, I could look at them, compare them to the 3D model. When we gave devices back, it became more challenging.”

"I love the projects we get here – every day it’s something new, and I feel like I’m helping my community by being part of UNMC and iEXCEL."

Anthony Lanza, 3D artist

Lanza, who is currently working on a project for the UNMC College of Dentistry, puts in a lot of research before creating virtual 3D models. He came to UNMC from the gaming industry as a modeling/texturing software expert, and he said he enjoys working to facilitate medical education.

“I like teaching and research,” he said. “Transitioning from gaming to working in higher education – I was previously at Bellevue University – was great for me. I love the projects we get here – every day it’s something new, and I feel like I’m helping my community by being part of UNMC and iEXCEL.

“I got to model a device to help people with their anxiety before they have to get brain surgery. To me, that’s more rewarding than, ‘Oh, there’s the bottle I modeled in the background of that video game.’”

Rieke, who has been involved in deep brain stimulation at UNMC since 2006, said Lanza wasn’t overstating the device’s potential impact.

“There’s a noticeable difference when people have gone through a procedure before as to how comfortable they are,” Rieke said. “This is a simulation, obviously, but just having a little experience goes a long way in making people feel more relaxed.”

Deep brain stimulation can be a life-changing surgery, Rieke said. He has seen bedbound patients able to travel again, patients able to drink from cups without lids for the first time in years. But it is an elective surgery – patients must decide they are prepared for the challenges of the procedure.

“Anything we can do to help them with that preparation is an advantage,” he said.

iEXCEL doesn’t do a lot of modeling for 3D printing, Glass said. But when they brought Lanza’s virtual model to the McGoogan Library’s makerspace, the library’s Brian Maass was happy to assist.

“I had to adapt the model, which was in a visual format,” Maass said. “The 3D printer uses a framework of triangles that the computer sends to it. So I had to get the model into a format the system would understand.”

Glass said Maass’ input was invaluable.

“This would not have been possible without Brian’s knowledge and passion,” Glass said. “The tests and problem-solving that he worked out allowed him to produce and deliver an elegant solution.”

Brian Maass, assistant professor and digital technologies librarian at the McGoogan Health Sciences Library, displays the 3D printed replica of the stereotactic head from and fiducial localizer box, to be used to help patients overcome anxiety as they prepared for deep-brain stimulation surgery.

The result was a realistic looking, though somewhat lighter, replica of the head frame and box that delighted the team. Dr. Weeks’ group and the neurology department each have one. The prototypes are so realistic that Dr. Weeks thinks they may eventually become standard tools across the country for addressing pre-DBS anxiety.

“Previously, we’ve done things like watching videos of other people being prepped for the surgery, so patients would have some sense of what is happening, but we didn’t have anything this tangible,” Dr. Weeks said. “This is going to be helpful – because you always want to be able to engage in exposure in advance of the situation and learn to adapt to that anxiety and prepare.”

Drs. Aflagah, May and Weeks said they are delighted with the device – and the patients they’ve talked to are eager to try it.

“I’m quite pleased with how it looks from a neuropsych perspective,” Dr. Aflagah said. “It’s nice to have something concrete to show people and have them try on. It makes us better able to assess. We’re still relying on self-reporting, on how they feel they’re going to react, but the model will help patients be more objective.”

The duo said they are ecstatic with the results of the multidisciplinary collaboration.

“We are very grateful,” Dr. May said. “It was exciting to see how these other departments responded to our request and cared so much about helping our patients.”

Dr. Weeks agreed.

“This kind of teamwork, all in the cause of patient care – this is why UNMC is a special place.”

Aviva Abosch, MD, PhD, chair of neurosurgery, said she was grateful to the team “for making the effort to create this device that is being used to educate and allay the concerns of our patients. I am excited to see what benefits derive from this project.”