Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a leading risk factor for heart attacks and strokes. It affects almost 30 percent of the population worldwide, and is often treated with multiple drugs, at high doses, with potentially significant side effects.

|  |

Alicia Schiller, PhD | Yiannis Chatzizisis, MD, PhD |

|  |

Peter Pellegrino, MD, PhD | Hanjun Wang, PhD |

Now, a multidisciplinary team of UNMC researchers is working on an innovation that could turn a once-promising idea into a game-changing breakthrough. A drug-free hypertension treatment.

Renal nerves deliver signals from the fight-or-flight centers of the brain to the kidney, contributing to high blood pressure. This fact was well-established from animal models of hypertension; removal of these nerves by an invasive surgical procedure reduced or normalized blood pressure.

“There are preclinical studies showing this is effective,” said Yiannis Chatzizisis, MD, PhD, professor of cardiovascular medicine.

|

Irving Zucker, PhD |

Thus, the development of minimally invasive, catheter-based devices to destroy these nerves in humans generated extraordinary excitement, drawing billions of dollars of private investment from major medical device companies.

But the first pivotal clinical trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed no blood pressure difference between the renal denervation and a placebo procedure.

The consensus was that the patients in this early trial simply did not receive effective treatments.

“This is not like a stent or a new valve where you can instantly see the effects of the intervention. You have no idea if you’ve performed a successful (renal denervation) procedure or not,” said Alicia Schiller, PhD, assistant professor of anesthesiology, the project’s principal investigator.

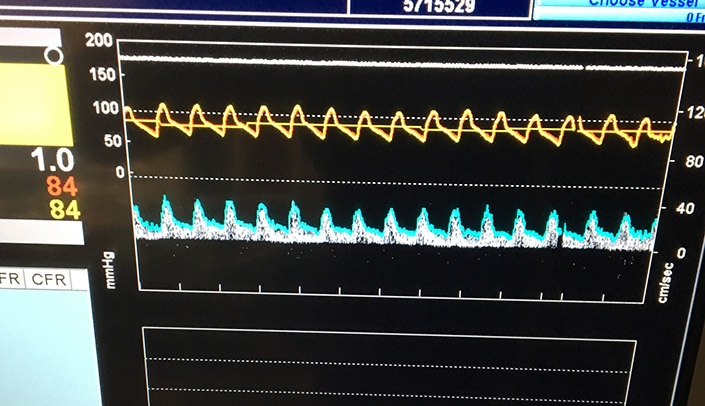

Dr. Schiller, anesthesiology resident Peter Pellegrino, MD, PhD, their mentor, Irving Zucker, PhD, professor of physiology, Dr. Chatzizisis, and Hanjun Wang, PhD, associate professor of physiology, invented software that uses blood pressure and flow signals from the kidney artery to see if these renal nerves were still functional. Using this technology, we could know immediately whether the procedure was effective. If not, the patient would receive another round of denervation.

This new validation technology, coined “sympathetic vasomotion,” is safe, quick and uses the data from a common catheter. “Nothing fancy,” Dr. Chatzizisis said.

This idea was born from Drs. Schiller’s and Pellegrino’s dissertation work, with Dr. Zucker, and flourished with Dr. Pellegrino’s technical expertise and engineering background and Dr. Chatzizisis’ interventional cardiology expertise. Their invention is patented with help from UNeMed, UNMC’s technology transfer and commercialization office.

The team’s original studies were funded by a Nebraska Research Initiative grant and published in Hypertension in October. These studies used invasive surgical denervation and pharmacological interventions to destroy or block the renal nerves, both of which could be detected with their technology.

So, would it work when a catheter-based device is used to destroy the nerves?

To find out, they teamed up with the device company Medtronic, to compare the effect of surgical renal denervation with renal denervation using Medtronic’s Spyral” catheter. “If the technology works in these preclinical studies, the next test will be in the human cardiac catheterization lab,” said Dr. Chatzizisis, who performs the catheter-based renal denervation in animals.

If successful, this technology could be applied to other abnormalities of the sympathetic nervous system to treat a wide variety of diseases.

WOW! That is exciting. Keep up the good work!!