Benjamin Terry received an engineering master’s degree from Colorado School of Mines, then applied for jobs in the business sector: automotive and medical devices. He landed for nine years in the medical industry, developing electronic mechanical devices, such as dialysis machines—even though he had no knowledge of biomedicine.

"I grew to love that business, because everything we shipped directly helped people," he said.

But it wasn’t enough.

He wanted to do more than implement devices other people invented.

He wanted to be the inventor.

As a result, Dr. Terry moved from industry to academia, so he could work on the creative, innovative side of medical devices. He earned a doctorate in mechanical engineering from the University of Colorado Boulder and forged specialties in medical therapeutics and surgical tools, intuitive ambulatory biosensors and biomechanical behavior of tissues and organs.

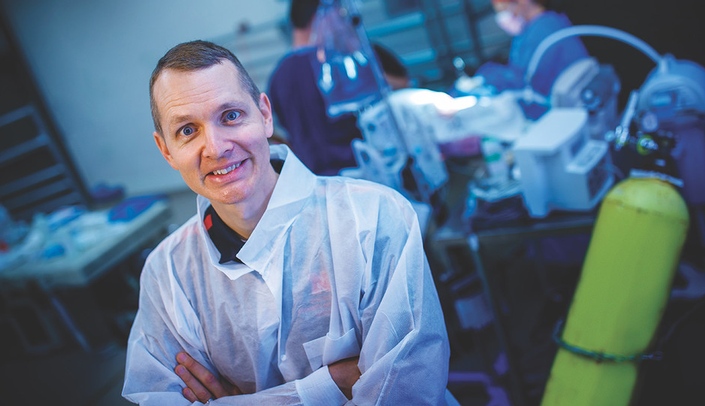

Today, Dr. Terry is associate professor and principal investigator at the Terry Research Laboratory (TRL), University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL). The lab develops new engineering technologies that support biomedicine and literally save lives.

Among many exciting projects, with one of his University of Colorado professors, Dr. Terry has become known for developing new technology that delivers oxygen microbubbles to traumatized lungs. Dr. Mark Bordon invented the microbubbles, and Dr. Terry invented the concept of using them as therapy for injured lungs.

"It has been gratifying to bring new concepts into existence," he said. "Most engineers are detail oriented. I tend to be more oriented toward the big picture. I like to be involved at the beginning of the project and nurture it, then hand it off to someone else for implementation."

In tandem with his university role, Dr. Terry serves within a cadre of elite researchers tapped for national and global defense missions through the National Strategic Research Institute (NSRI) at the University of Nebraska.

The Terry lab lends NSRI and its sponsors significant research and development personnel and tools for rapid prototyping, fabrication and testing of biological materials linked to defense missions. The lab also offers the benefit of rich partnerships with world-class surgeons and medical personnel through collaboration with the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), the Center for Advanced Surgical Technology (CAST) and across UNL.

In 2016, the office of the Air Force Surgeon General awarded NSRI a $1.3 million contract to advance the new medical microbubble oxygenation treatment process. Dr. Borden was asked to create a process and system for large-scale manufacturing of microbubbles. Dr. Terry was responsible for designing and developing a medical device to deliver them to patients. UNMC surgical critical care specialist and associate professor of surgery, Dr. Keely Buesing, was tasked with developing injury models to test the new technique. In a weapons of mass destruction event with mass casualties, this technology could increase survival rate.

Dr. Terry and Dr. Buesing have collaborated on numerous projects, their specialties often soundly complimenting one another with notable outcomes.

"Dr. Terry looks at every problem with a critical eye and is ridiculously talented at bringing novel solutions to the table," Dr. Buesing said, citing Dr. Terry's drive and focus as personal strengths.

"His contributions to novel therapeutic options in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) hold the potential to transform clinical treatment algorithms," she said.

In other words, Dr. Buesing explains, Dr. Terry's work offers brand new options for critically ill patients, with both civilian and military benefits.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, the two collaborated on her idea for putting two patients on a single ventilator.

"We happened to have a model up and running, with people already trained," Dr. Terry said. "This doesn’t exist in more than a few places around the world."

During the pandemic, with NSRI’s help, Dr. Terry also received permission to use a Department-of-Defense-funded machine to produce thousands of face shields for a local hospital. NSRI added funding to make it happen.

Dr. Terry’s defense projects all contain a crucial element of synergy marshalled by NSRI.

"The United States is huge and complicated," he said. "There are many folks who have a great ability to solve problems, but if no one knows about the problems, they won’t get solved. And you don’t want five groups trying to solve the same problem. NSRI helps ensure someone hasn’t done it already."

To continue the stream of quality engineering NSRI and its partners demand, Dr. Terry hires engineering graduate and undergraduate students in the top 15% of their class for the lab. His goal is to carefully nurture and prepare them for action.

"We are like a military special forces unit," he explained. "You can’t produce trained personnel in mass quantities in a short time. You have to have a pipeline.

"It’s the same with engineering. You can’t just stamp out an engineer overnight who can solve these types of high-impact problems. We nurture a long-term training relationship with each student that hopefully spans most of their academic careers."

For Dr. Terry, developing future engineers is key to the success of his lab’s cutting-edge inventions. And key to saving lives and helping people—just the kind of business he can love.

In the Business of Helping People: Engineering Inventions and National Defense

- Written by NSRI

- Published Jul 13, 2020