|

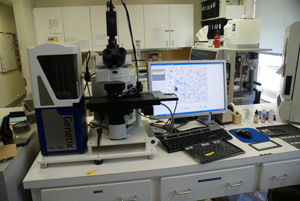

A new slide scanner in the MMI Human Genetics Laboratory can scan up to 120 slides unattended without stopping. There are just 18 of these scanners in the world. |

|

Christine Higgins, a core cytogenetic technologist in the MMI Human Genetics Laboratory, analyzes metaphase cells on her computer. Skilled cytogenetic technologists are vital to the process of determining if a specimen contains an abnormality. It’s just that before the slide scanner, microscope time took up a significant part of the process. |

There are just 18 “Genetix” scanners in the world and only two allow for patient information to be entered utilizing a bar code system — one of which is in MMI’s lab and the other in Edinburgh, Scotland. Other systems must enter the information manually.

The machine works by automatically scanning numerous images of metaphase cells within minutes, whereas before, a cytogenetic technologist had to spend hours behind the lens of a microscope searching for metaphase cells on a slide.

“The machine doesn’t do it all though,” said Warren Sanger, Ph.D., professor and director of the UNMC Human Genetics Lab. “Skilled cytogenetic technologists are still vital to the process of determining if the specimen contains an abnormality. It takes an experienced professional to analyze the metaphase cells and make a diagnosis.

“Before, microscope time was taking up a significant part of the process. Now our technologists can spend more of their efforts on analysis.”

“Scope time” as it’s affectionately referred to in the lab will not be missed by many of the technologists, including Christine Higgins, a core cytogenetic technologist in the laboratory.

“It can cause headaches, neck pain and nausea,” she said. “It’s very physically demanding.”

“Prolonged scope time can be tedious and eye-straining and is not ergonomically friendly,” Dr. Sanger said.

Because the slide scanner can scan up to 120 slides without stopping, Dr. Sanger said it will allow experienced cytogenetic technologists to nearly double their efficiency and productivity from approximately 250 cases per year to 500.

“It’s a quantum leap in our field in terms of efficiency,” Higgins said.

“The new technology will definitely create an opportunity for us to grow,” Dr. Sanger said, emphasizing that the technology will not eliminate positions, but will allow the lab to process more cases and possibly reduce the cost of genetic testing without sacrificing accuracy.

|

|

This isn’t the first time the human genetics lab has been at the forefront of groundbreaking genetic technology.

“We were one of the first labs to validate microarray technology for clinical use and now we’re one of the first to utilize this new technology,” Dr. Sanger said. “I foresee it eventually becoming routine in genetics labs.”

And to add to the good news in the lab, the University of Nebraska Board of Regents recently approved the purchase of a new data management system.

The system will allow reports to be entirely electronic. This “green” move will save between 200 to 300 diagnostic reports and attached supporting documentation from being printed each day. Dr. Sanger hopes to have the system in place this year and fully operational in 2010.