|

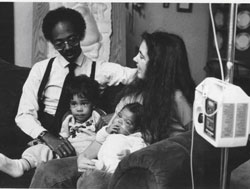

Morgan Smith-Dennis on his mother’s lap at home with his family in 1986 shortly after receiving a liver transplant at UNMC. |

|

A young and healthy Morgan, left, playing with his brothers. |

|

Morgan Smith Dennis – in the leather jacket — with the basketball team he coached last winter. |

Twenty-one years ago, Morgan Smith-Dennis went home a typical 7-pound newborn. His parents, Moses Dennis and Mary Smith-Dennis had all the joy and hope of new parents. Things were settling in with life with a newborn in Olathe, Kan.

They started to suspect something was wrong when their newborn would sleep most of the time and was very jaundiced. When they took him for his one-week checkup, the pediatrician ran routine tests. One came back indicating a problem with the liver.

He referred the family to the children’s hospital in Kansas City, Mo., where tests revealed tyrosinemia, a hereditary disease that brings on a protein deficiency, causing liver and sometimes kidney disorders, among other things.

“You could just tell he was not well,” said Mary Smith-Dennis. “We never dreamed he would need a transplant. We thought it was some kind of virus that medications would take care of.”

When Morgan’s condition deteriorated, he was admitted to the intensive care unit in critical condition. Physicians there phoned UNMC’s Byers “Bud” Shaw Jr., M.D.

“I don’t think there was a question of not doing it,” said Dr. Shaw, who a year earlier had started UNMC’s liver transplant program. “It was a child who was desperately ill, who needed a liver transplant. We didn’t consider that he was too small.

“The difficulty in a child that size, at that time, would have been finding a donor organ. Not only were tiny donors very rare, but also most of the babies in such a small size range would have been very ill prior to death, so the quality of organs was not likely to be good,” Dr. Shaw said.

Morgan flew in a medical helicopter and arrived at UNMC late in the evening of June 17, 1986, said Mary Smith-Dennis. The family met with Dr. Shaw and his team about 10 p.m.

Moses Dennis, Morgan’s father, remembers the experience like it was yesterday. “The doctors said there were 48 hours to get a donor,” he said. “The room was full of docs and it didn’t look good. No one had ever put a liver in a two-week old. I was thinking, OK, what’s the good news?”

“There was no other hope at that point,” said Mary Smith-Dennis. “There was no one else in the country on the organ donor waiting list at that size.”

But at 9:30 a.m. the next day they were told there was a donor.

“It was one of the happiest days in our lives,” said Moses Dennis, who also knows it was a tragic day for the donor family. “I thought it would work out and we’d be home in a few weeks.”

The family was happy to have a donor, but also knew the transplant would only be the beginning of a potentially long struggle.

In the operating room, Dr. Shaw and the team began the very intricate and delicate surgery, using 10 power magnification glasses to operate.

“The connection for the artery is the smallest one — probably a millimeter to a millimeter-and-a-half. We’re talking about a blood vessel that’s maybe as big around as a refill cartridge of a ball point pen,” Dr. Shaw said, “and we had tiny little stitches that look thinner than a human hair.”

The family waited and waited.

They remember the transplant team well, particularly Dr. Shaw and Laurie Williams Salonen, who at the time was nurse coordinator for the program.

“(Dr. Shaw) had that poker face but you knew when he was concerned, and you knew when he was in an upbeat mood,” Moses Dennis said. “I also remember Laurie Williams, our nurse. Morgan was in surgery from 5 p.m. until 5 a.m. the next day. Laurie would give us updates every-hour-on-the-hour on how things were going.”

Once Morgan got out of surgery, doctors came to talk with the family.

“Man, they looked beat,” Moses Dennis said.

For the next six months, Morgan was hospitalized — three-and-a-half months of it was spent in and out of the intensive care unit.

“It was a rough course,” Mary Smith-Dennis said. “He had six more surgeries after the transplant for perforations and a bowel obstruction. He had an abscess in his new liver.”

He was in a coma after his second surgery. His kidneys weren’t working right. At his size, there were challenges with oxygen, nutrition issues and the immunosuppressant drugs that would keep his body from rejecting the donor liver.

The couple remembers living day-to-day, hour-to-hour.

“It seemed like one crisis or problem after the other,” Mary Smith-Dennis said. “It also seemed like the doctors were able to figure out and deal with them.”

Salonen, who now is manager of liver and intestinal transplantation, said she remembers the family well, particularly Mary Smith-Dennis, who spent most of the six months at the hospital.

“She took on the role of comforting others and didn’t let things get her down,” Salonen said. “Morgan didn’t have an easy post-operative course, yet she always maintained a calm and positive attitude and really was mentor and support for other families despite what was going on with her child.”

Though Morgan was small and fragile, Salonen said she was not surprised he survived.

“Everyone here did their very, very best to make sure that this child had every possible chance of surviving,” Salonen said. “That is the type of team we have here at the University of Nebraska.”

There was another silver lining in the cloud.

The city of Omaha took the family under their wings. Moses Dennis said it seemed like the entire city came to their aid. News reports about the family quickly spread.

They made friends in the community and in the hospital. People would take their 3-year-old son to the toy store. Churches hosted Sunday dinners. They would see people around town who said they were praying for the family.

Though it’s been 21 years now, and the family lives in Minneapolis, they have never forgotten what Omaha means to them.

Morgan Smith-Dennis’s 21st birthday celebration was a quiet, family gathering.

Morgan’s been healthy, other than being hospitalized for an episode of rejection at around age 2, and for chicken pox. “He’s healthier than the rest of the bunch,” his mother said. “He’s just tough.”

And Morgan’s three brothers don’t cut him any slack. “It’s amazing,” she said. “We look back and think of how normal life is and how far we’ve come.”

Morgan graduated from high school a few years ago and works in an athletic fitness facility. He’s also training for a career in helping elementary school-age children with emotional and behavioral issues.

“He has a gift for building relationships with kids,” Mary Smith-Dennis said. “He’s very sociable and empathetic.”

Though Morgan Smith-Dennis doesn’t remember much about the transplant, what he remembers are the check ups over the years, and the transplant reunions where he and his family were reacquainted with other transplant families. He remembers hanging out at the hotel, eating at the reunion luncheon, the balloons and games.

Most people wouldn’t know he’s a transplant recipient, unless he tells them, they ask about the two daily pills he takes or inquire about the large scar on his stomach. His friends know and it’s no big deal.

Once in a while, he thinks about the fact that he had a transplant and the donor family who saved his life.

“I’m thankful,” Morgan Smith-Dennis said. “It’s a really special thing. I always wanted to meet them. I would love to do that.”

He will see Dr. Shaw and Salonen today, but doesn’t know what he’ll say beyond “thank you.”

Like other members of the transplant profession, Salonen and Dr. Shaw are gratified by being able to make a positive impact on a person’s life.

“That’s why we are all in this business,” Salonen said. “We are here because we believe in what we do and believe we can help people live a normal life. We are incredibly blessed to be able to be part of these peoples’ lives.”