|

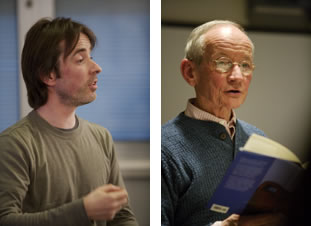

Artist Mark Gilbert, left, and former U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser have helped with a UNMC program aimed at teaching future physicians to have better observation skills. |

To really understand what’s happening with a patient, it is vital that the physician function like a detective – look for every possible detail that might provide a clue.

“Observational skills are probably the most difficult thing for medical students to learn, and yet, they are probably the most important skill they can have,” said William Lydiatt, M.D., a head and neck cancer surgeon in the otolaryngology-head and neck surgery department at UNMC.

|

He hopes to do as many as 35 patients and 35 caregivers, then turn the portraits into an exhibition, much like the “Saving Faces” exhibition Gilbert previously did depicting head and neck cancer patients in the course of their treatment. The Saving Faces exhibition came to Omaha in 2006. One of the patients Gilbert drew was Sebron Kendrick, who suffers from AIDS and bouts of depression as a result of his condition. Kendrick found his sessions with Gilbert to be therapeutic. “I enjoyed it,” he said. “I always looked forward to seeing Mark. It invariably lifted my mood.” Gilbert is serving as an artist in residence at the Bemis Art Gallery in Omaha this spring. Funding has been identified to allow him to continue his teaching at UNMC and UNO during the 2007-08 academic year. |

Over the course of three classes, nearly 20 third-year medical students and resident physicians learned new techniques for observing patients by listening to a Scottish artist and a Nebraska poet.

“You have to empty your mind of any preconceptions before you start drawing. You need to react to what’s in front of you,” said Mark Gilbert, the Scottish artist who has come to Omaha to teach both at UNMC and the University of Nebraska at Omaha. “It’s like the golfer with the yips, he can’t empty his mind. You need to get in a zone. If you ask a soccer player how they scored a goal, they usually can’t recall. They were just in a zone.”

“It’s all in the detail,” said Ted Kooser, the Nebraska artist who last year completed a two-year stint as the national poet laureate for the United States. “I try to move my writing from fuzziness to clarity. I may go through 30 to 40 versions before I finish a poem. I know it’s finished when no part of the poem can be changed without weakening the poem.”

A Pulitzer Prize winner, Kooser also serves on the faculty of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Eight years ago, he was treated by Dr. Lydiatt for tongue cancer. “UNMC and Dr. Lydiatt saved my life. I owe them immensely,” he said.

For his class, Kooser gave each of the students a green pepper and a plastic knife and asked them to take 20 minutes to observe the pepper, cut it open and then record their observations in minute detail.

“You have to think about who is on the other end of the communication, about who is going to read what you have written,” Kooser said. “You don’t get to accompany your writing and explain it. Among other things, you have to get into the detail to make things clear. Always, in writing, if I write ‘there were three chickens on the road,’ you have a much better image of what I’ve said then if I just write ‘there were chickens on the road.'”

Gilbert taught the first and third class with Kooser teaching the middle class. Each class also featured a simulated patient. Students were asked to observe the patients and share their observations. In addition, the students were asked to keep a journal over the course of the month-long project and to use drawings and writing to help make observations on the patients they encounter.

“The power of observation gets better over time,” Dr. Lydiatt said. “The ideal time to learn is to go back and do something again after you’ve already done it. That’s the best way to teach someone how to do a surgical procedure.”

|

Medical students and resident physicians take part in a drawing session led by artist Mark Gilbert. |

“Drawing is one of the most profound ways of communicating. It is an amazing way to make students responsible for their work,” he said. “Every mark you make is a direct and honest response to what you’re looking at.”

Drawing is a skill that is foreign to most of us and especially medical students whose brains are trained to memorize information rather than create things, Dr. Aita said.

“Students may be so left-brained that the drawing might not come easily to them,” she said. “It’s a challenge, but that’s what makes this special.”

The students were told to take their time when making a diagnosis. “It’s important you don’t zero in on the diagnosis right away,” Dr. Lydiatt said. “It’s easy to immediately go to a diagnosis, then try to support it. You need to be careful. You want to try to observe as blankly as possible.”

The class had a profound impact on the students.

“The light bulb went on for me in the final class,” said Katie Lazure, a third year medical student from Sioux City, Iowa. “When you force someone to draw for 15 minutes, you notice things you may not have previously.”

For Karel Capek, a third-year medical student from Milligan, Neb., it’s a lesson that he’ll remember throughout his medical career.

“Anyone can read an EKG once they’ve been trained,” he said. “Learning how to observe a patient is a whole other thing. It’s probably the most important skill a physician can have. I think the class was very worthwhile.”

One of the take home messages was the power of the arts. Kooser wrapped up his session by telling the students: “I returned to poetry to restore order during a chaotic time of my life (his cancer treatments). I knew as soon as I started writing that fall that I was going to be OK.”