Many theories exist about why people, mostly children, get myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle that causes mild to severe disease, including death or the need for a heart transplant. The theory of a UNMC research team is featured as the cover story in the May 15 issue of the Journal of Infectious Diseases.

|

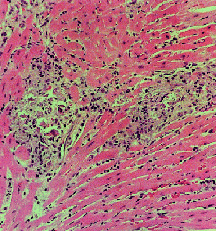

Murine heart histology resulting from infection with a cardiovirulent strain of coxsackievirus B3. |

What is significant about the team’s discovery is for the first time, it allows scientists to identify a piece of coxsackievirus B that controls its ability to grow in heart cells.

“That will allow us to better understand how the virus replicates and possibly develop better treatments or vaccines for myocarditis,” said José Romero, M.D., pediatric infectious disease specialist and senior author of the article.

Coxsackievirus is classified as a human enterovirus that occurs naturally among human populations. It can cause flu-like symptoms. But in its worst form, it can cause acute myocarditis, aseptic meningitis, severe infections in newborns and severe hepatitis.

He said this is only the second time for the family of 64 enteroviruses that scientists were able to identify a region of the viral RNA that controls its ability to cause disease. The polio virus was the first.

The team’s quest is to understand why some strains of the coxsackievirus B are harmful while others are not.

Beginning in the summer and lasting through October, the majority of coxsackievirus myocarditis cases will strike from 5,000 to 7,000 people, mostly children. About one-third of those diagnosed with myocarditis recover, another third recover but have some or significant damage to the heart, and the other third die. The condition is also the cause of death of a number of people each year who suddenly collapse and die, such as athletes.

Dr. Romero, who also serves as director of the UNMC/Creighton University combined division of pediatric infectious diseases, said the virus is the most frequent cause of acute viral myocarditis, a serious disease that causes inflammation of the heart muscle, and dilated cardiomyopathy, in which the heart becomes quite large. The problem is that not much treatment is available.

The study is a collaboration among Dr. Romero, and authors Steven Tracy, Ph.D., Nora Chapman, Ph.D., and former graduate students, James J. Dunn, Ph.D., and Shelton Bradrick, Ph.D. The journal, published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, is the premier publication in the Western Hemisphere for original research on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of infectious diseases; on the microbes that cause them; and on disorders of host immune mechanisms. It represents physicians, scientists and other health care professionals who specialize in infectious diseases.

Drs. Romero, Tracy and Chapman have been studying coxsackievirus and enteroviruses since the 1980s. Several years ago, they set out to understand why one strain of the coxsackievirus causes disease but another strain doesn’t.

In the study, they swapped the viral genetic matter (RNA) of myocarditis — causing coxsackievirus strains with that of non-myocarditis-causing coxsackievirus strains. Dr. Romero said the virus that could cause myocarditis grew well in the mouse heart, whereas the non-cardiovirulent strain did not grow. They found different strains of the virus perform differently in the mouse heart.

“A crucial interaction must occur between the virus and the heart cell in order to cause disease,” Dr. Romero said. “All of these findings indicate where we should be looking to understand more about this disease. It also tells us what’s different about different cells. We think it may be that the virus can’t copy its RNA well. It tells us there’s something inside the heart muscle cells that the virus needs to grow.”

Dr. Chapman, associate professor of pathology and microbiology, said the team has found a tiny structure in the RNA genome critical for allowing the virus to cause heart disease.

She said the reason the findings are important is a lot of the virus strains don’t cause disease. “One of the things we want to know is if someone gets infected with coxsackievirus, are they more likely to end up with myocarditis,” Dr. Chapman said.

One of the problems with myocarditis is few treatments are available. An experimental drug exists, but mostly, Dr. Romero said, patients are given supportive care such as drugs that make the heart beat stronger or take the load off the heart. Artificial devices that perform functions of the heart also are used. Those include an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine or ventricular assist device.

Dr. Romero said the team used a novel approach to study the virus. He said while most experiments done for decades on the virus relied on laboratory strains of coxsackievirus, the strains are no longer found. The team instead used strains in the lab from humans who had disease.

“The question always arises if findings in the lab really apply to clinical situations,” Dr. Romero said. “Our idea was to use ‘wild’ strains from people to test and figure out what part of the virus causes cardiomyopathy.”

One of the things that drew Dr. Romero to UNMC in 1993 was the research of Drs. Tracy and Chapman. He saw several opportunities to work and learn from them, he said.

For Dr. Romero, whose clinical and research interests have focused on enteroviruses, specifically coxsackievirus and myocarditis, the discovery means a lot.

“What we’ve done is found the switch. Now we want to figure out how the switch turns the virus on or off,” he said.

The team currently is in the process of applying for funding from the National Institutes of Health to identify the mechanism that determines the causes of cardiomyopathy, how many cases there are, the causes and outcomes.