Stephanie Nigro was 23 years old and a recent architecture graduate when her ophthalmologist told her she had keratoconus, an eye condition that leads to vision loss.

“I left there totally hysterical,” Nigro said.

In the time before computer CAD design, architects such as Nigro would create eighth- or quarter-inch images as they worked out their designs. Nigro, who had just moved to New York City, was facing the potential loss of both her vision and her career.

Keratoconus results in the deterioration of the cornea over time. As the disease advances, the cornea thins and becomes more cone-shaped, like a football.

Nigro soon learned that corneal transplants offered a cure for keratoconus. After taking time to build up her design company in New York – “I don’t know if it was denial or just the energy of youth, but I just continued on with my life” – she had her first corneal transplant five years later.

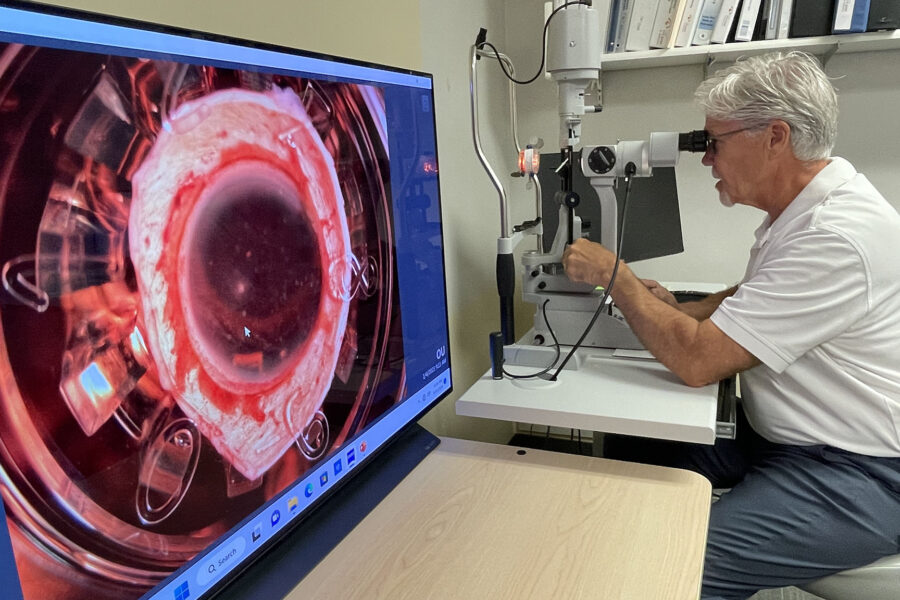

This past year, Nigro, now retired and living in Florida, traveled to Omaha for her fifth transplant, following UNMC’s Ronald Krueger, MD, who has worked with her for decades on retaining her vision. It was one of 3,000 surgical procedures performed at the UNMC Truhlsen Eye Institute last year, many of which are sight-restoring – including corneal transplants, cataract surgeries, retinal detachments and vision correction procedures.

“It really gives a person hope, to know that these options are available,” Nigro said. “It’s important to realize that in the case of keratoconus, as well as other vision problems, there can be opportunities for a cure.”

“The first doctor I saw never said anything about a transplant. He never said, ‘There’s a cure down the road.’ It was horrible. I left there feeling my life was over.”

Dr. Krueger calls the sight-restoring operations a profound confirmation of an ophthalmologist’s mission.

“Vision improvement or restoration – as ophthalmologists, we are doing that all the time,” he said. “The beauty of ophthalmology is that sight is so valuable to people, and if you do procedures where you can get a quick return of vision, it’s a profound experience, both for the patient and for the doctor.

“Cornea transplants don’t immediately give good vision. It takes multiple months for the vision to come back. But cataract surgery, laser vision creation correction, you can give almost immediate vision, where people come the next day and go, ‘Wow, I can see everything.’ That is, honestly, a cool thing.”

For Nigro’s most recent surgery, the donated tissue came from the Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska, where Karli Diggins earlier this year was named executive director.

Diggins, who has been with the eye bank for three years as a tissue procurement specialist, took over the role in April. The Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska has been located on the UNMC campus since 1960 and facilitates approximately 250 transplants a year in Nebraska.

Diggins said the eye bank’s staff specialize in two preparatory procedures – DSEK (Descemet’s Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty) and DMEK (Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty), as well as processing full thickness corneas for transplantation. She and Curt Coughlin, whom she called “the foundation of the eye bank,” are the only two non-physicians in the state trained to prepare DMEK and DSEK corneal tissue.

“In the DMEK preparatory procedure, we peel the back membrane or layer of the cornea, and the surgeon transplants it directly into a recipient to restore their vision,” Diggins said. “It’s one of the more recent surgery techniques – it results in a lot less recovery time for the patients and a much quicker response as far as being able to see.”

DSEK, an older procedure, involves taking a thicker portion of the back of the cornea to make a layered graft, which replaces more of the cornea than just the thin membrane, so it requires a little longer recovery time.

The patient’s condition and the surgeon’s input determine what type of surgery is best for the patient, Diggins said.

The eye bank has done DSEK since 2010 and has performed 2,182 grafts to date this year. The relatively newer DMEK procedure has been offered since 2017, with 527 grafts completed this year to date.

(Coughlin, who has been on staff for 40 years, is not the eye bank’s only stalwart. Staff member Cindy Retallick, a tissue procurement specialist, has been there 23 years, while Angie Bashus, the quality assurance coordinator, celebrated 20 years of service this year.)

The eye bank works closely with the region’s ophthalmologists, including those at the Truhlsen Eye Institute on the eastern edge of UNMC’s Omaha campus, Diggins said.

Dr. Krueger stressed that the eye bank is there to serve the entire community, although there are academic and research advantages to having the building on campus. As the chair of the UNMC Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and board member for the eye bank, he also is working to raise funds for a new facility.

“The clinical aspect of what the eye bank brings is self-evident, but there is research and education going on throughout the department of ophthalmology, and the eye bank helps with that,” he said.

Currently, the Lions Eye Bank is advancing the work of Shan Fan, MD, assistant professor in the UNMC Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, who works on glaucoma devices and implants.

“We have been supplying whole globes, for her to practice putting those implants in and getting data,” Diggins said.

Researchers who use the “whole globe” – all of the eye – often can, when their research is complete, supply other parts of the eye, such as lenses and retina, to other research projects, Diggins said. So, one donation may end up supporting many areas of research.

Dr. Fan’s research focus is glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness.

“Mainly, glaucoma is caused by high eye pressure, because high pressure can damage the optical nerve. This damage is irreversible,” Dr. Fan said.

“Our glaucoma lab focuses on studies to better understand the causes of glaucoma and how that affects the fluid flow within the eye. We use this information to investigate medications and drainage devices to lower eye pressure and slow the progression of the disease.”

One of the lab’s current studies pursues the effects these devices have on fluid drainage performed in donated human globes – how easily the eye’s natural fluid (aqueous humor) flows out of the eye before and after putting the implants.

“The eyeball is like a balloon in that it is filled with fluid under pressure,” Dr. Fan said. “The aqueous fluid is created and flows inside the eyeball, and then out through its drainage system. If the aqueous flow has high resistance, the drainage system has issues, and it causes pressure that can damage the optic nerve. And in the early stage, there are no noticeable symptoms. That’s why we call it the silent blinder.”

Dr. Fan’s team is exploring different methods of reducing aqueous buildup by increasing aqueous flow through the inner wall of what is known as Schlemm’s canal. They work with devices and stents as small as one millimeter in size, similar to the tip of a sewing needle or the thickness of a credit card.

“We measure the resistance of the fluid drains of the eye, how the flow gets through Schlemm’s canal,” she said.

Of course, research is only part of the advantage of an affiliated eye bank. “Although the Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska is an independent eye bank, it is affiliated with the Lions Club and cooperates with eye banks across the nation,” Dr. Krueger said.

“If I have a transplant scheduled for a young patient, then I need a young cornea. What if my bank doesn’t have a cornea for me? Do I reschedule and hope that next time there will be a cornea available? The Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska can go nationwide and say, ‘Hey, we have a need.’ And a Lions Eye Bank in Wisconsin or in California can say, ‘Yes, we can help with that.’

Krueger notes that corneal transplants are the most frequently performed transplant surgery across the country.

“They have the least chance of rejection. They have good availability of tissue. And they don’t really require special biomarkers to match with someone else. Was the donor healthy? Is the donated tissue somewhat age appropriate?”

The Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska’s mission, restoring eyesight, would not be possible without organ and tissue donation, Diggins said. In fiscal year 2023, the bank had 430 eyes donated, and 235 in fiscal year 2022.

“We’re very thankful for all the donors that we get,” Diggins said. “This is an ongoing effort that greatly increases our ability to provide tissue for these life-enhancing surgeries.”

Nigro said, “The option of having corneal transplants gives a patient hope, which is crucial to one’s mental health. Of course, successful transplants also are coupled with the gift of independence.

“I don’t want to depend on my children. I want to be able to live my life. I’ve given up things in my life that I used to enjoy because of the keratoconus, sure, but the surgeries have had a big impact.”

Nigro said she is often frustrated by the lack of awareness of the impact of eye donation.

“It is essential for people to be aware that when they donate, they’re not just giving a cornea. They’re not just giving good vision. They’re giving a person a life. The gratitude I have for people who donate the corneas, and the gratitude I have for the doctors and the procedures and the research …”

She’s also indebted to the eye bank. “I don’t want to forget the Lions Eye Bank and how grateful I am to them,” Nigro said.

Diggins knows that the idea of donating eyes may seem off-putting to some.

“My goal is to create more awareness about what we do, the precision and care that is taken with these gifts, and all the good that it does,” she said.

And as a partner with the Lions Clubs International, the Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska can send out a call for certain tissue if needed or supply needed tissue to eye banks across the country and the world.

“That’s an awesome partnership to ensure these gifts get used, because the goal is restoring sight, and we’re excited we can be a part of that,” Diggins said.

Learn more about the Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska and register to be a donor here or at the Nebraska Department of Motor Vehicles.

Great Story! We are proud of our Lions Eye Bank of Nebraska (LEBN)……

Thank you to the donors and the families who say yes to giving the gift of sight! Talk to your family about your wishes.

Absolutely! Nothing possible without their selfless generosity!

Wow Kurt, who knew you were the foundation of the eye bank!!! Well, I did. It’s 100% true! It looks like a lot of things have changed since I was there. Congrats on 40 years as well!

Thanks Kitty! Hope you’re doing well! My time here is winding down, but yes, eye banking has changed dramatically. Most of the transplants require the advanced processing, which is something I truly enjoy. Tammy retires in March and I’ll hang on a little longer, but not too much : )

I had such wonderful care at the Stanley Truhlsen Eye Institute. Thanks to the Amazing Drs. Chundury, Nelson and Wilson, and great Nurses.

thanks

CONGRATULATIONS to all of the LEBN staff and board of directors for all you do to help preserve one of nature’s most precious gifts – vision!

Kal Lausterer

Great article Curt ! Just think how many lives you have helped over the 40 years. You’re truly a gift yourself !