I still remember the “regulars” from my high school job at a local fast-food restaurant.

Of those few, some stand out more than others.

Like Justin Bainbridge, a young man with Down syndrome.

Bainbridge came in for lunch with his mother every Sunday after church. And more than a decade later, I still remember his order — a cheeseburger with ketchup only, fries and a drink.

Everyone wanted to be the one to wait on Bainbridge when he strolled up to the counter. Partly because of the grin you’d see on Bainbridge’s face if you recited his order before he could. But also because he was so personable, independent and kind.

Now I’ve come to realize I’m far from the only person that Bainbridge has left a lasting impression on.

In fact, he has far exceeded any expectations set for him and blown by any fears that his diagnosis would “hold him back.”

He learned to read.

He has a job.

He can navigate his neighborhood for his daily walks.

He lives in his own apartment.

And the 34-year-old, joined by his mother, Kim Bainbridge, has become one of the city’s most active Down syndrome self-advocates and educators.

Kim Bainbridge has been speaking to high schools, college and other organizations about Down syndrome since Bainbridge was 10 months old. Bainbridge began participating actively when he was in the ninth grade. Now, the two of them speak to between 200 and 300 people each semester, working together to combat stereotypes and misinformation about the capabilities of children and adults with Down syndrome.

“Our story has evolved to providing examples of what adults can do,” Kim Bainbridge said. “But the gist of our message always has been the same: that Justin is more like other people than different.”

Kim Bainbridge counts herself as one who, at times, underestimated her son.

“He has far exceeded what anyone ever expected of him,” Kim Bainbridge said. “Even myself. But I was always willing to try, and I surrounded myself with other parents who also had high expectations for their children.”

When Bainbridge was born in the late 1980s, it was still common for children with Down syndrome to be sent to a facility in Beatrice, and school districts didn’t quite know how to handle students with disabilities, she said.

But the Munroe-Meyer Institute gave her hope.

Kim Bainbridge met with Warren Sanger, PhD, founder of the genetics program at MMI, and Bruce Buehler, MD, former director of MMI, in the weeks after her son was born.

“At MMI, it’s always been positive,” Kim Bainbridge said. “It’s always, ‘Let’s achieve it. Let’s go for the gusto.’”

Bainbridge has received services at MMI since he was born. Over the years, he’s taken part in genetic counseling, speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy and psychology services.

Now he participates in adult recreation programming, including cooking, art, yoga and Wheel Club, the recreational bike-riding club.

When Bainbridge decided he wanted to live independently, he and his mother Kim eased into the challenges head on by breaking things down in small, incremental pieces. He would stay home alone for a couple hours at a time. He learned to wash his own laundry and clean the house. He would grocery shop and prepare his own meals. He and his future roommate also practiced going to movies alone.

Bainbridge and his roommate initially signed a three-month lease at an apartment complex near southwest Omaha. The duo still lives on their own, in the same complex, 11 years later.

There is some support provided at the complex. Brian LeFebvre, a staff member, spends 25 to 30 hours a week with Justin.

“I am not here to do things for Justin,” LeFebvre said. “I am here to make sure he does things for himself. I don’t clean his apartment. I don’t wash his clothes.”

Bainbridge has a busy schedule. LeFebvre takes him to his job in the Millard North High School cafeteria, where he is affectionately known as “Scoopy” for his speed at filling cups with canned fruit and snapping lids on. On average, he fills between 300 and 400 cups a day.

LeFebvre has seen growth in Bainbridge’s confidence on the job, adding that many adults with developmental disabilities provide value in the workforce.

“Justin is not doing them a favor,” LeFebvre said. “He is a valued employee who comes in and does a job.”

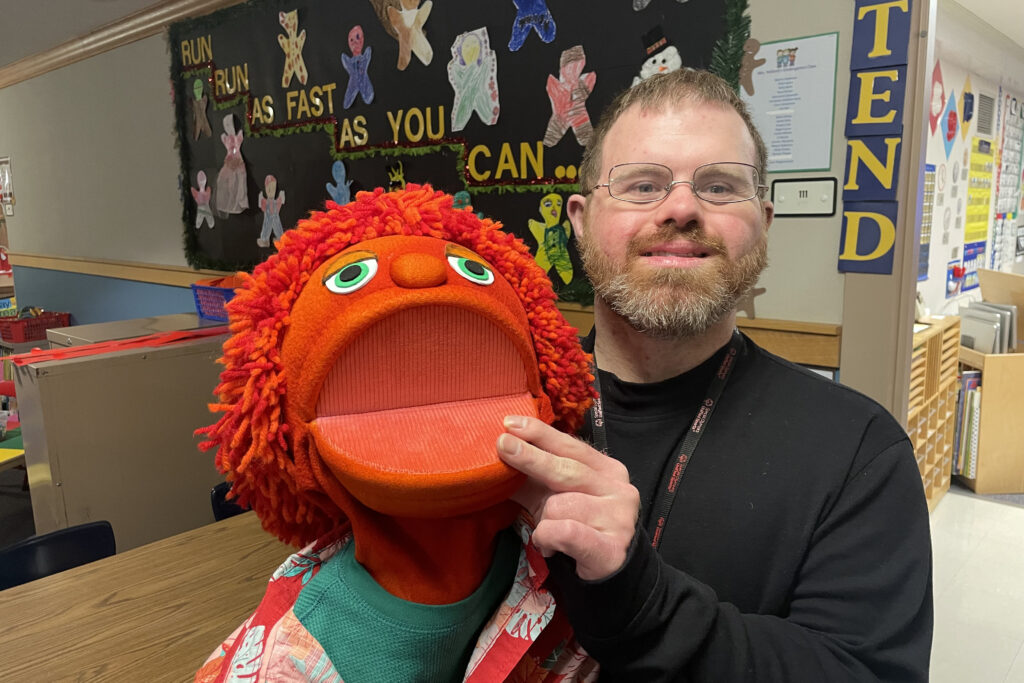

Other signs of independence: Bainbridge walks to book club with his roommate and has logged a solo plane trip to Seattle to visit his sister. He also is a member of a puppet troupe through WhyArts, which provides inclusive arts education events in the Omaha area. His puppet, Jayden, also has Down syndrome.

“There’s always going to be a long way to go, but the sky is the limit,” Kim Bainbridge said.

LeFebvre echoed that. “You don’t know what people are capable of until you allow them to be capable of it.”

Justin has been instrumental in the lives of his family members, too. He’s taught his niece and nephew that everyone has value. His brother coaches Justin’s baseball team. His sister went into speech therapy. And his mother has fought for inclusivity.

“If God said, ‘I’m going to take away that extra chromosome,’ all of us would say, ‘Absolutely not.’ Justin has taught us so much more,” Kim Bainbridge said. “He’s taught us perseverance and empathy.”

While they didn’t remember me when we met in Justin Bainbridge’s apartment for this story, I remembered them.

Cheeseburger. Ketchup only.

Fries and a soda.

Just a week later, I connected with the Bainbridges at the Walk & Roll for Disabilities, where they have one of the event’s largest teams.

Bainbridge held down the fort at one of the team’s tables, his charismatic smile almost contagious. Radiating a sense of purpose and an unquenchable optimism as he spent the day with his MMI friends.