When Thang Nguyen, PhD, came to the UNMC Department of Emergency Medicine in 2010, he almost immediately started looking for ways to do things better.

Dr. Nguyen, then a nursing fellow, was watching a plastic surgeon suturing a wound on the face of a young girl.

“This was a physician trained in the art of precision suturing, and in the end, the wound repair was superb,” he said. But he noticed that, as meticulous as the surgeon was, there was quite a bit of tugging and pulling of the patient’s skin with each stitch.

“I thought, ‘Why can’t we invent something that would minimize the movement of your wrist as you’re moving the needle through tissue?’” Dr. Nguyen said.

Turns out, someone else had thought of that, too. Dr. Nguyen didn’t discover that, though, until after he had meticulously drawn up his version of what is known as a needle driver and submitted it to UNeMed for evaluation.

“Within weeks, I got word back – someone’s already thought of it.”

But Dr. Nguyen had, in his words, “been bitten by the innovation bug. Once I submitted that form and got into the UNeMed process, it was such fun I just kept going.” Dr. Nguyen even gone as far as prototyping his version of the needle driver using components from BIC pens and a lot of super glue.

Dr. Nguyen dates his drive to innovate from his childhood as a first-generation immigrant.

“I remember wanting a lot of things that were always out of financial reach,” he said. “This motivated me to learn how to think outside of the box early in my childhood. I remember making my version of Legos out of scrap wood found around our home or fixing broken toys found on the side of the road. I feel like I’ve carried this innate drive to ‘fix’ things into my career as a health care provider.”

He focuses on developing technologies that could aid in eliminating health care disparities and improving global wellness.

Nearly 14 years after that first inspiration, UNeMed President and CEO Michael Dixon, PhD, acknowledged Dr. Nguyen as one of the tech transfer agent’s top idea generators.

“If I had to build a prototype inventor, it would look a lot like Dr. Nguyen,” Dr. Dixon said. “He does exactly what all successful inventors do. He keeps taking swings at new ideas. Some work out and some don’t, but he just never stops. That relentless pursuit of finding new and better ways is what it takes to help improve health care.”

Michael Wadman, MD, chair of the UNMC Department of Emergency Medicine, agreed.

“Thang not only is a prolific inventor, but he is also a mentor and leader for innovators at UNMC and in our community,” Dr. Wadman said. “He fosters creative thinking and clinical problem solving in others and leads groups of innovators to achieve more collectively than they would have on their own.”

While Dr. Nguyen doesn’t hold the most patents, at the end of the 2023 fiscal year, he had filed the most New Invention Notifications (NINs), the first step in the patenting process, with 70. Howard Gendelman, MD, chair of the UNMC Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Neurology, had filed 69 and is the current UNMC investigator with the most U.S. patents, and Dr. Nguyen’s own department chair, Michael Wadman, MD, has filed 60. (No other UNMC investigator has filed as many as 40.)

Dr. Nguyen downplays the number.

“Basically, that means I’ve come up with 70 crazy ideas,” he said with a laugh. “But if one of my 70 crazy ideas can help someone, I feel it’s worth a group discussion to push innovation forward.”

And those ideas? Not always crazy. Dr. Nguyen and his emergency medicine colleagues got their first patent in 2019 for an innovative wound irrigator, hooked to an air system, that provides a consistent saline stream at an optimal 13 to 14 PSI.

Today, Dr. Nguyen and various emergency department colleagues have filed 17 provisional patents, six U.S. patent applications, and three international patent applications. Dr. Nguyen has been awarded two patents, with another three patents currently in the approval process. His most recent issued patent is for a new COVID-19 testing device.

“During the pandemic, the quality of specimens collected via the nasal swab was all over the place,” Dr. Nguyen said. “And a big part of it was patient hesitancy — no one liked the nasal swab, it was painful, and patients oftentimes would either pull back, resist or just flat out refuse testing.”

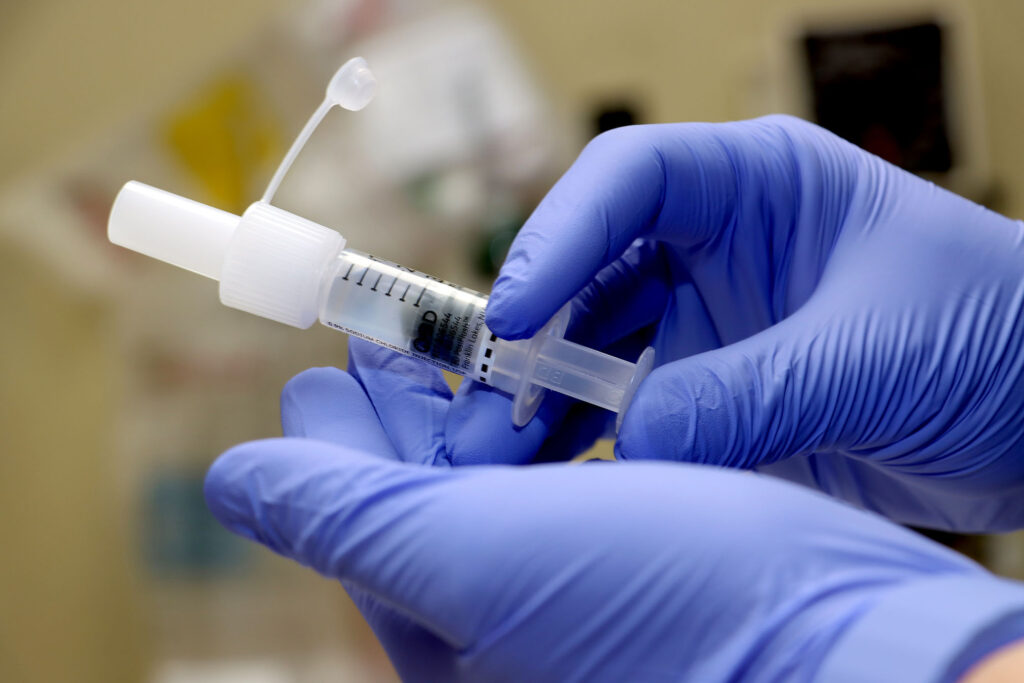

Dr. Nguyen’s new product, the Microwash, drew inspiration from the wound irrigator.

“The wound irrigation literature demonstrated 13 PSI or so can debride the skin of bacteria. So, I thought, ‘What if we did the same thing for the nose? What if, instead of a swab, we sprayed water into the nose at a certain PSI? That could debride the nasal tissue for viruses, and we can use that for testing instead.”

It’s taken more than four years, but the MicroWash is the department’s first innovation success story. After refining the design, working through manufacturing and distribution woes, the MicroWash is finally on the market. The department has done studies showing that the test results are comparable in accuracy to results using the swab.

“Specimens collected with the MicroWash were just as good as nasal swab specimens when testing for viruses, but more importantly, patients preferred the MicroWash,” Dr. Nguyen said.

Although he has filed the most NINs to UNeMed, Dr. Nguyen stressed that many of those NINs have co-inventors from within the emergency department.

“When I come up with ideas, I run them by other people within the department – What do they think? Is it viable?” he said. “What I love most is when they poke holes in the idea because I can design around potential flaws in my original concept. And when I talk to someone and they poke enough holes in the idea, to me, they are now a collaborator. So, at that point, if I haven’t already submitted the NIN, I include them because it’s important to cultivate a collaborative culture.”

Dr. Nguyen said he doesn’t see himself – or his ED colleagues – as more creative than other UNMC departments. Perhaps, he said with a laugh, they are more dissatisfied.

“I want to say, in terms of the innovative spirit, every department has it,” he said. “That said, in emergency medicine we are trained and taught to think on the fly. You never know what emergency is coming through the door, so you’re always doing the best you can with the supplies in hand to optimize patient care.”

“I sometimes say jokingly – jokingly! — that in emergency medicine, we are complainers,” he said. “We love to complain. But – and this is where the culture of this department really has an impact — we may complain, but then we have people here who will get together and say, ‘If no one likes this process, how do we improve upon it? If it’s a process or a whole new device we have to improve — or even create — let’s do something about it.’”