Like many faculty researchers, Annemarie Shibata, PhD, an associate professor of cellular neuroimmunology and director of the undergraduate neuroscience program at Creighton University, had numerous concerns when the university shut down in mid-March due to COVID-19.

How would she continue her research?

Who would be allowed in the lab?

How would she continue teaching her classes?

How would she continue mentoring her students?

"It’s certainly been a challenge," Dr. Shibata said. "Normally, I have about nine to 12 students in the lab at any one time, but all that changed with the pandemic."

While Dr. Shibata had experiments to tend to that brought her into the lab once a week, her classes in immunology and neurophysiology lab and special topics in neuroscience went online.

And those students who were conducting experiments had to cease going to campus and switch gears, meeting on Zoom to discuss papers they are writing and how to safely gather data.

"We continued working on submitting abstracts to the Society of Neuroscience annual meeting that takes place in Washington, D.C. in the fall," Dr. Shibata said.

Through it all, she said her overall goal was to continue to give all of her students the resources they needed to keep learning.

Whether that meant assigning background readings, or YouTube clips to watch where they could learn different methodologies that they could apply once they did return to the lab.

"I wanted to keep the students engaged and active so when they do return to the classroom or lab we have hopefully mitigated the upward learning curve that can happen during down times," she said.

As for the students, Dr. Shibata said she has not sensed any lack of enthusiasm.

Some of her students were allowed back into the lab in mid-June and eagerly dove right back into their research.

Dr. Shibata’s lab is focused on three projects. The project funded by the INBRE Developmental Research Project Program, focuses on the study of CPT2, a specific enzyme found in the mitochondria that normally contributes to metabolic cell signaling and plays a particular role in postnatal brain development.

Dr. Shibata is particularly interested in a metabolic disorder that occurs when a mutation blocks the normal function of CPT2 that may contribute to attention deficit disorder and schizophrenia.

"Our hope is that down the road as we gain a better understanding of the pathogenesis of CPT2 mutations, this knowledge will lead to drug therapies that could treat these cognitive and neuropsych disorders," she said.

Her lab uses zebra-fish to generate the mutations of interest and study how they react to different drug therapies.

"The students really like working with the zebra-fish because they can inject the fish embryo with a construct and see the mutation occur during development and into adulthood," Dr. Shibata said.

She works in collaboration with Holly Stessman, PhD, in the department of pharmacology and neuroscience at Creighton University, and Ken Kramer, PhD, who is director of the zebra-fish core lab and associate professor of biomedical sciences at Creighton University.

"Drs. Kramer and Stessman are really good at helping bridge the gap in understanding how the construct works so the students can work effectively on their experiments," Dr. Shibata said.

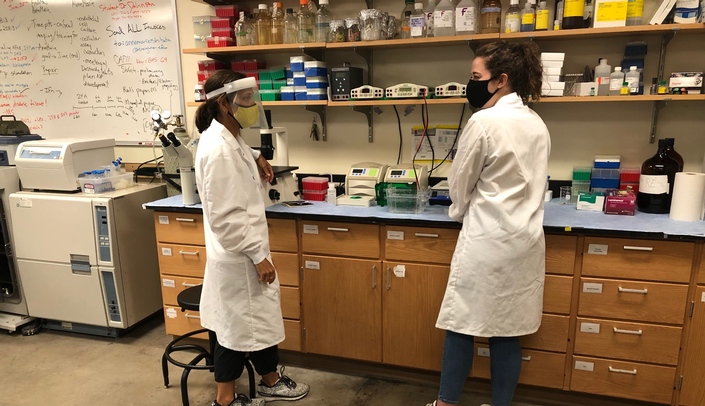

As school resumes, Dr. Shibata said she has a rotating schedule set up among her students with only four to five students coming into the lab at any one time so they can maintain physical distancing and still conduct their research.

"Our goal is to stay safe and do good research," she said.

Conducting Research During a Pandemic Can Be Tricky Says One INBRE Researcher

- Written by Lisa Spellman

- Published Aug 14, 2020

Dr. Annemarie Shibata, at left, talks with undergraduate research student, Carly Baker, in her lab at Creighton University, while adhering to social distancing and other COVID-19 CDC recommended safety guidelines.