It was early March, and Creighton Blue Jays fan James Faylor, M.D., and his son went to New York City to watch their favorite team play in the Big East Tournament.

The United States was just starting to grapple with the COVID-19 virus with the first reported case of coronavirus on Jan. 21 in the state of Washington.

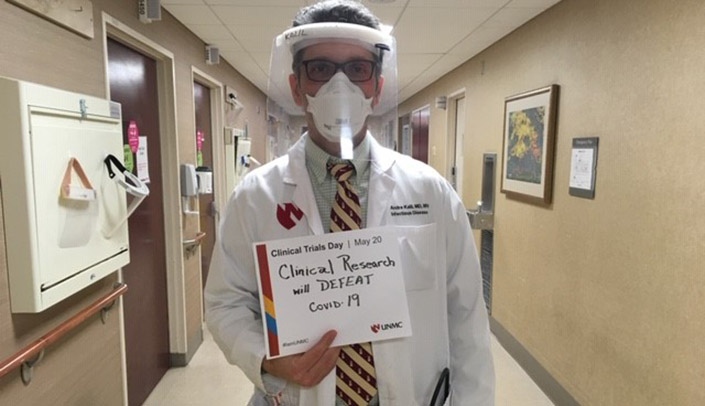

Clinical Trials Day

Celebrated around the world today, Clinical Trials Day is a way to recognize the people who conduct clinical trials and say “thanks” for what they do every day to improve public health.

Like many Americans, Dr. Faylor was aware of what was happening, but had only heard of one other smaller outbreak on the east coast involving a woman who had traveled to Iran.

“The Blue Jays only got to play half of their game, and then it all got canceled and everyone went home,” he said.

That was on March 12, and by the following Monday, March 16, Dr. Faylor had developed a cough and called the health department hotline to inquire about a test.

Within seven days of testing positive for COVID-19, Dr. Faylor was laying in the intensive care unit at Nebraska Medicine, intubated and fighting for his life.

Daniel Lemos, an auto repair shop manager, had been feeling a bit feverish when he inquired about getting tested at a drive through site being held at Fonner Park in Grand Island in early April.

His father was hospitalized with COVID-19, and he suspected that his increasing shortness of breath and fevers were related.

Lemos drove to Fonner Park on the morning of Good Friday, April 10, and by that evening he could barely drive to the hospital, his breathing had become so difficult. By the next day he was on a life-flight to Nebraska Medicine, where he would be put on a heart-lung machine.

Both Dr. Faylor and Lemos would spend weeks in the hospital, much of that time sedated as doctors and nurses did all they could to keep them alive while their bodies fought the virus.

Both families were approached and asked if they would consent to their loved one taking part in a new clinical trial.

The clinical trial testing remdesivir versus placebo was on the fast track as a potential drug therapy in treating COVID-19 with some early promising results.

Their families agreed to their participating in the study, not knowing if their loved one would get the drug or not.

As it turns out Dr. Faylor did receive the medication, something he credits for saving his life.

Lemos did not, but is glad his family was willing to enroll him in the trial.

“Clinical trials are a way to help everybody, and even though I didn’t get the medication, I would still participate if given the opportunity,” Lemos said.

Dr. Faylor agrees.

“I’m sure Remdesivir helped me and if the shoe was on the other foot I would do the same for my family member,” he said.

“The medications used in clinical trials are usually studied for years before being tested in humans thus the fact we were able to complete this large trial in less than two months is a major advance in the discovery of new treatments,” said Andre Kalil, M.D., physician and primary investigator of the National Institutes of Health clinical trial of remdesivir at UNMC.

In the case of remdesivir, with the gravity of the situation facing the world, the Food and Drug Administration gave emergency use authorization for doctors to use it in patients who have COVID-19 because it showed promise in early tests, Dr. Kalil said.

I have worked as a colleague/research coordinator with Dr. Faylor in past clinical trials for Stroke, and am happy to see that he benefitted from participation himself. Carolyn Peterson