Elizabeth Wellsandt, D.P.T., Ph.D., assistant professor of physical therapy education, in the College of Allied Health Professions, is looking for limps and hitches so small, you’ll never notice them. The person walking doesn’t know they are doing them.

“It’s very subtle,” Dr. Wellsandt said. “You can’t see it with your eyes unless you’re in the lab testing it.”

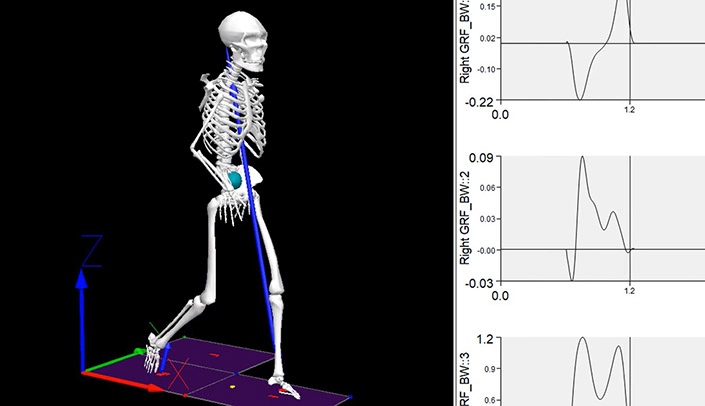

That would be UNMC’s Clinical Movement Analysis Lab (CMOVA). Dr. Wellsandt is director of the CMOVA lab.

She and her collaborators are looking for these imperceptible differences in gait among young people recovering from anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries.

It’s the interdisciplinary team’s (see sidebar) hypothesis that these slight differences have a cumulative effect. This effect, and less movement in general, might contribute to young people with an ACL tear having a high risk for developing arthritis in the knee within 10 to 15 years.

When we hear of ACL injuries, we may think of our favorite college or professional athletes who have had what Dr. Wellsandt calls “remarkable comebacks.”

But the full picture is, only two-thirds of people with ACL tears ever return to their pre-injury level of activity.

For many young people, that full picture may include the onset of arthritis over time, too.

The team is studying patients with ACL tears from before surgery through a time at six months after ACL reconstruction, to check their progress. They look for biochemical markers of arthritis. And, quantitative MRIs mark cartilage health.

Dr. Wellsandt believes the altered movement patterns, and decreased movement in general, may contribute to unhealthy cartilage in the short term — and arthritis down the line.

And then there is the specialized analysis in the CMOVA lab to track any invisible, unconscious compensation for the injured knee. The team is also using activity monitors to track how much patients are moving outside of the lab.

Patients may look perfectly normal, Dr. Wellsandt said. “But, their brain can find ways to unload their injured leg without using their knee – they compensate with their hip or ankle muscles instead.”

And that could throw everything off.

Dr. Wellsandt is watching for these changes, and any results.

Her project is funded to the tune of more than $600,000 with two significant grants – an R21 award from the National Institutes of Health, and an Investigator Award from the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

The study is currently on pause due to social distancing during the global COVID-19 pandemic, but will be ramping back up once the situation allows.

Great work!

So proud of your work, Liz!