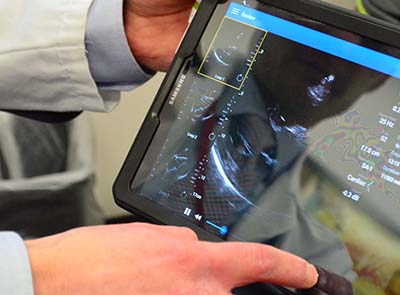

Internal medicine physicians and residents are starting to make their hospital rounds with another tool that can help them make diagnoses — point-of-care ultrasound.

|

The point-of-care-ultrasound system can see fluid around the heart, size of the heart chambers, heart valves and whether the heart is beating normally. |

POCUS, which helps physicians make diagnostic and management decisions at the bedside, has been around for about two decades in emergency rooms. But in the past five to 10 years, it’s grown into other areas of medicine, driven partially by technology making the devices smaller and more portable, said Christopher Smith, M.D., assistant professor of internal medicine and co-director of the POCUS program.

“In internal medicine, it’s still a relatively new application, but it’s growing,” Dr. Smith said. “Our program is one of the early adopters of providing internal medicine residents robust training in POCUS. Our goal is to teach health care providers how to integrate POCUS into their clinical decision making and ultimately improve the care of our patients.”

He said POCUS can be used to help make a diagnosis, do screening, monitor response to therapy and guide procedures. The machines range in size from hand-held to more sophisticated versions on a cart.

“How you use it depends on the context and the question you need answered,” said Dr. Smith, who works in the UNMC Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Hospital Medicine. “I can see inside of a patient and use that as one more piece of data to consider when I’m making decisions.

“For example, if a patient is admitted with trouble breathing, I can quickly get a sense of how well their heart is pumping or if there is evidence of a pneumonia in the lungs. I can also use sonography to more safely perform procedures, for example to collect a fluid sample from inside the abdomen.”

He said there are plenty of other applications, everything from looking at the bladder and kidneys to joints and soft tissue abscesses.

“There’s a lot of information I can gather very quickly when I’m at the patient’s bedside with my little machine,” Dr. Smith said. “I still may get a formal diagnostic study to get more detailed information, but if I can get some basic information at the bedside, it can expedite the proper treatment for the patient.”

He and co-director of the POCUS program, Tabitha Matthias, M.D., are training residents and a core group of faculty in general internal medicine to serve as teachers for the residents.

POCUS training also is being integrated into the new College of Medicine curriculum so medical students will graduate with ultrasonography skills, Dr. Smith said.