UNMC College of Medicine graduate Ronald Hamilton, M.D., describes what happened this way:

“My student handed me a small pebble, and said, ‘Is this what I think it is?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And I threw the pebble to the ground.

“And it started an avalanche.”

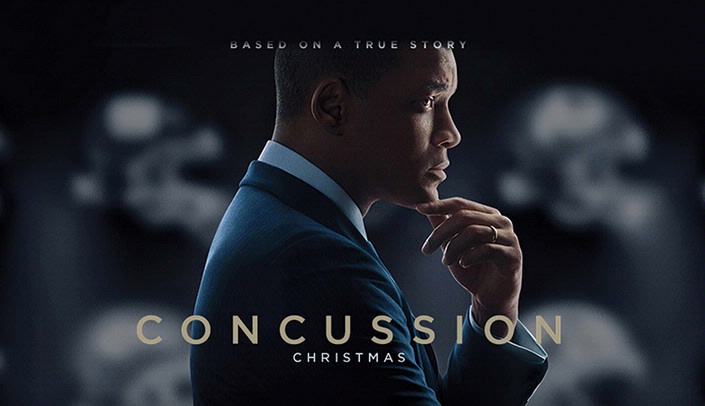

The “pebble” resulted in a groundbreaking discovery on traumatic brain injury. This new finding changed the way we look at one of our national pastimes, football. It led to controversy, a national conversation, and eventually, a movie, “Concussion,” starring two-time Oscar nominee Will Smith.

The movie also has a “Ron Hamilton” character. The Omaha native (Omaha North, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, UNMC Class of 1989) is part of this story, too.

Dr. Hamilton’s mentee, Bennet Omalu, M.B.B.S., had gone to extraordinary measures to make a discovery that changed everything. But, Dr. Hamilton was the senior scientist who confirmed the discovery and staked his reputation on it.

When the National Football League, through its Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, demanded a retraction – a rarity in science – “My career was on the line,” Dr. Hamilton said.

It began in 2002, when Mike Webster, a Pro Football Hall of Fame player, died at age 50 after suffering from what he himself had previously called football-related dementia.

Webster’s body came to the Allegheny (Pennsylvania) County Coroner’s Office, where Dr. Omalu worked.

Already a forensic pathologist, Dr. Omalu had invested several years of further training with Dr. Hamilton to also become a neuropathologist. He wanted to distinguish himself within the field. “Really, a go-getter guy,” Dr. Hamilton said.

Dr. Omalu, an immigrant from Nigeria, did not know who Webster was. “He didn’t know football from baseball,” Dr. Hamilton said. But if the man on the table before him had suffered from dementia, Dr. Omalu felt he owed it to Webster to look at his brain.

This was unusual. Most times, cause of death would be considered “natural,” and that would be it. Dr. Omalu got the OK to investigate further, but was told he needed to work on Webster’s brain on his own time, on his own dime. He did, in part working with Dr. Hamilton’s lab at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, where Dr. Hamilton is director of the neuropathology core and an associate professor of pathology.

“True Blood” star Stephen Moyer has said in interviews that he wanted the part of Ron Hamilton because of the crucial scene between Drs. Omalu and Hamilton.

Dr. Hamilton said there are certain cases neuropathologists see all the time. And then there are those

you see only in textbooks, or once in a lifetime. In Webster, Dr. Omalu had found the latter.

Dr. Omalu stopped by Dr. Hamilton’s office to confer with his mentor – to present the pebble. Dr. Hamilton recalls being given the slides “blind,” with no other information. Just tell me what you see.

Dr. Hamilton is known worldwide, within the field, for having made strides in the study of Alzheimer’s disease. He’s an expert. Looking at the slides, he ticked off what this case wasn’t. At last, he came to a conclusion.

Dementia pugilistica. A boxer.

No, Dr. Omalu said. This was a football player. This was Mike Webster.

Oh, of course. Then and now, it made perfect sense. “It didn’t even phase me,” Dr. Hamilton said.

It would be interesting to see how many times former football players had been diagnosed with this condition, Dr. Hamilton said.

Dr. Omalu already had checked the literature. The answer was zero. Mike Webster was the first.

“That’s when my jaw dropped,” Dr. Hamilton said. “I knew, right at this point, this was not going to be the last case. There were going to be lots of other cases.

“No neuropathologist had ever looked at the brain of a football player before.”

The avalanche was starting…

Ronald Hamilton, M.D.

Dementia pugilistica no longer sufficed. This was new. In consultation with Dr. Hamilton, Dr. Omalu coined the term chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. (Technically, dementia pugilistica is a form of CTE.)

And, as they wrote up this first case study for publication, Dr. Omalu and his collaborators knew to tread carefully.

“When you submit a paper to a journal, the standard practice is they will send it to two reviewers,” Dr. Omalu said, in an interview with PBS Frontline. “If the two reviewers agree this is a good paper, it’s published. They’ll make some comments, make some changes.

If the two reviewers disagree, it’s sent to a third reviewer and majority wins. Do you know the number of people that reviewed this paper? There were over 18.”

“It was an incredible peer review process,” Dr. Hamilton said. “That just made it stronger. When the paper got published we were very happy about it.”

Not everyone was. A handful of physicians, who coincidentally served as the National Football League’s Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee, wrote the journal demanding a retraction.

“That’s like a nuclear option,” Dr. Hamilton said. “When you demand a retraction you are saying it’s faked, it’s false, incorrect to such a degree.

“We were stunned.”

Dr. Omalu later said that as he read the rebuttal, he realized something. These doctors, none of whom worked with the brain, were not on solid ground scientifically.

And then something else happened. Another former Pittsburgh Steeler, Terry Long, died tragically and too young. His body also came to the Allegheny County Coroner’s Office. A colleague saved the brain for Dr. Omalu.

Long also was found to have CTE.

Then, another former pro football player killed himself. When Dr. Omalu examined his brain, CTE. Another, killed in a car crash after an incident with police. CTE.

And another. And another.

“When we got that first case, we didn’t really understand what the magnitude was going to be,” Dr. Hamilton said. “I thought that maybe one in 100 or one in 500 might get it. I didn’t think it was going to be as pervasive.

“It’s kind of like the California gold rush,” Dr. Hamilton said. “Why had no one discovered gold before? It was right there. If you weren’t looking for it, you won’t see it. But if you know to look for it, you’ll see

it everywhere.”

Ron Hamilton, M’89, with “Concussion” director/screenwriter Peter Landesman, who visited the neuropathology offices at the University of Pittsburgh several times to prepare for filming.

More cases rolled in. While some continued to doubt, other scientists eventually signed on, confirming and accepting CTE; some formed their own, quasi-competing research groups. All the while, Big Football continued to throw its weight into pushback of Dr. Omalu’s findings (just this year, after about a decade of denials, the NFL acknowledged a link between football and CTE).

Dr. Omalu, who hadn’t known what an avalanche this would cause, felt stress on multiple fronts. Yes, he was suddenly a famous scientist, but .

“It was a double-edged sword,” he told PBS, “because I began to be exposed to (these players’) lives. It started becoming personal to me. I started meeting the family members.” “He’s not just some distant pathologist looking at slides,” Dr. Hamilton said. “He’s involved with people.”

The emotion, the human drama, the politics, the public scrutiny could be overwhelming at times. There were days, he told friends, he wished he had never met Mike Webster.

“I said, ‘Bennet, you don’t know how many people you are saving because of this,'” Dr. Hamilton said.

“Neuropathologists know hitting your head is bad,” Dr. Hamilton said.

The brain, he explained, floats in fluid inside your skull. How does brain injury happen? “It’s not just the head-to-head hits,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It’s any time the brain is moving and stops suddenly.”

And that’s what happens when humans slam into one another, when they fall hard to the ground, when their necks snap quickly. In other words, what happens when they take part in contact sports.

The very title of the movie – “Concussion” – doesn’t tell the full story, Dr. Hamilton said.

Subconcussive hits, routine hits fans might not even notice, ones that happen multiple times every day in practice, also can contribute to CTE.

“No helmet in the world can stop the brain from moving around inside the skull,” Dr. Hamilton said.

Does that mean he believes football should be abolished? No. But make it an age-appropriate activity, Dr. Hamilton argues. Take all contact – all use of helmets – out of practices, so that the risk is limited to just several plays a week, several weeks a year, and only for the starters, who actually play in the games.

This is how you save America’s favorite sport.

The movie. “We knew it was Hollywood,” Dr. Hamilton said. “And we knew Hollywood was Hollywood.”

If you want to know the real story, all the nitty-gritty details, he recommends the book “League of Denial.”

But only a movie, only a star like Will Smith, could have the public impact “Concussion” had. “The most important thing the movie could do was increase the conversation,” he said, “and it did that.”

Now, almost everyone acknowledges CTE. Even those emotionally invested in football. Even the NFL.

And studies continue. “We know a little tiny bit about a little tiny bit,” Dr. Hamilton said.

More and more former football players have been diagnosed, via autopsy. So have victims of chronic domestic violence. Military personnel killed in combat.

But like Alzheimer’s, CTE can’t definitively be diagnosed until a person dies and scientists look at his or her brain.

“We’re at the very beginning of this,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It’s only been 10 years. It’s up to the physicians and scientists who work in living people to carry this on. We identified the disease in the dead.”