Major national and regional organizations have been trying to increase the number of positions for medical residents and shore up funding for all positions, but little progress has been made. Experts say now is the time to act because of the need to increase physician workforce and the continuing threats to funding for training residents – called graduate medical education (GME). Less money for training residents will mean less physicians and even more maldistribution of physicians in rural communities and urban underserved areas.

|

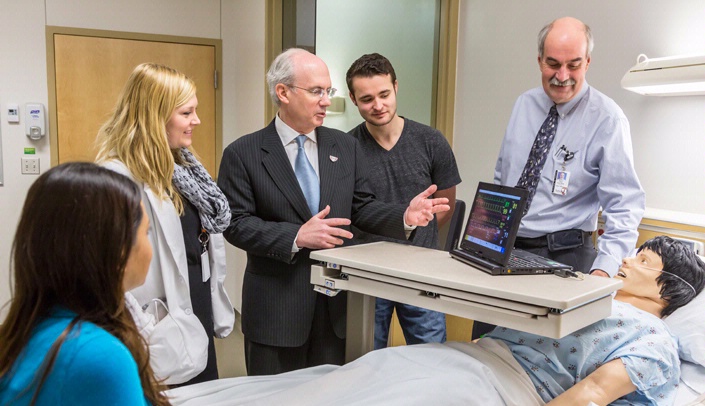

| Kelly Caverzagie, M.D. |

“We have actually created a point in time when it’s important to rethink quite radically how we do this process,” said Kelly Caverzagie, M.D., associate dean for educational strategy in the UNMC College of Medicine.

In a detailed report published Wednesday in Academic Medicine, UNMC Chancellor Jeffrey P. Gold, M.D., Dr. Caverzagie, and health policy expert James Stimpson, Ph.D., propose a different way of funding GME and medical school, often referred to as undergraduate medical education. They propose a comprehensive all-payer system. There’s been no recent literature that breaks down how to do it until now, Dr. Caverzagie said.

“The current system is not the best system with which to fund GME,” Dr. Caverzagie said. “Rather than the federal and state governments paying all the costs to train a resident, we believe that everyone who benefits from the health care delivery system should contribute to the cost of training residents since everyone benefits from a well-trained physician.”

Resident training

Residency begins after medical students graduate from medical school. For three to seven years, depending on medical specialty, resident physicians train under the supervision of a faculty member. The resident is the primary caregiver of patients and becomes a specialist through the residency training process.

“In addition to Medicare and Medicaid, the model calls for private insurance companies and all other health care payors to share costs.” The plan also suggests one answer to a long debated issue about medical school debt, which influences what specialty a physician chooses and where they practice – rural or urban. Debt also impacts the ability of underserved students to attend medical school. Dr. Caverzagie said a student who enters into medical school would have their tuition paid.

“When they graduate from medical school, they would have no monetary debt, but would be required to provide service in a place of need, whether that would be in a rural or urban underserved area,” he said.

Dr. Gold said the hope is to begin a meaningful dialogue for changes. He said the fine details would require years of studying and planning. “We hope that by publishing this manuscript we engage policy makers, legislators, as well as leadership in medicine, in a conversation that leads to further ideas and hopefully some pilot programs to develop partnerships on how we might reframe medical school funding and residency funding,” Dr. Gold said. “This is a high calling but desperately needed.”

Dr. Stimpson, formerly of UNMC, now is associate dean of academic affairs at the City University of New York School of Public Health.