When young Wolf Wolfensberger escaped Nazi Germany for Denmark, then later immigrated to the United States, he took a few things with him.

For the rest of his life, he kept them.

Turns out, he kept everything.

Turns out, he gave everything.

Wolf Wolfsensberger, Ph.D., was an extraordinary man. He came to America. He educated himself. He was a researcher at the former Nebraska Psychiatric Institute from 1964 to 1971 and a faculty member in the department of psychiatry that would later become part of UNMC. He would become a world-renowned advocate for, and expert on the care of, the developmentally disabled.

“He revolutionized services for people with disabilities,” said Mike Leibowitz, Ph.D., director of Munroe-Meyer Institute.

During a period when the developmentally disabled were routinely shifted off to institutions, literally cast off from society, he recognized their humanity.

We know he gave everything because he kept everything. He saved it all. The sheer volume is staggering.

When it arrived, the collection took up 1,584 square feet. “The size of a house!” McGoogan Library of Medicine head of special collections John Schleicher said.

Dr. Wolfensberger had worked at several places. After he died in 2011, most institutions looked at his collection and wanted portions. But only one – the McGoogan Library – wanted all of it.

Munroe-Meyer Institute, the Nebraska Developmental Disabilities Council and UNMC collaborated to take the entire collection. All the scratch paper. All the boxes. All the books. All the items. A lifetime worth of stuff.

Now, it is present day and another man is combing through it. Another man is starting to feel Dr. Wolfensberger’s passion. Another man may be finding his own life’s work.

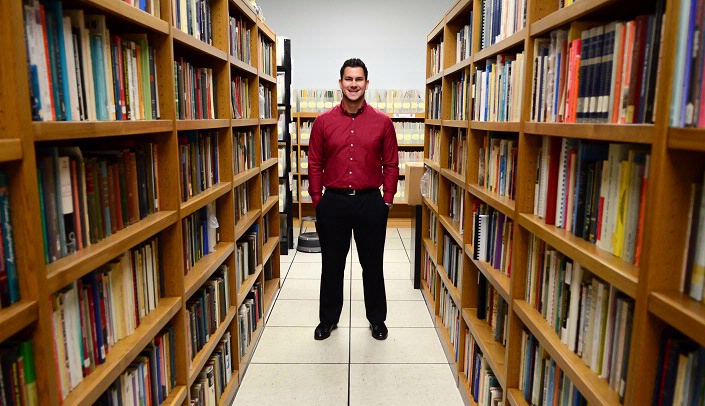

Of all the rarities within this collection, Cameron Boettcher believes he has become the rarest of them all.

“A history major with a job,” Boettcher said, and laughed. “That’s me.”

A library assistant in the McGoogan Library of Medicine, he tackles his Herculean task of unpacking, archiving, organizing, digitizing and curating the massive collection with a young man’s enthusiasm, wide eyes and bursting heart.

There were 35 filing cabinets; 450 boxes. There were 4,550 books and monographs, 598 journal volumes and thousands of file folders.

“Fifty years of advances for the developmentally disabled,” Boettcher said.

Because of Dr. Wolfensberger’s efforts, Boettcher said, people who otherwise would have been shipped to institutions are now in classrooms, working, living full lives.

Boettcher looked out over the collection, shook his head and grinned.

He’s determined to sift this vast collection into something the public can appreciate, so the world can see who Wolf Wolfensberger was, what he did and what his work meant.

Because he gave so much.