I asked him to take me to Kikwit, Zaire, back in the year 1995, to the second outbreak of Ebola-Zaire. To viral ground zero.

He closed his eyes and took a deep breath. He began to speak, slowly at first, and then his pace increased as images sharpened in his mind.

“Kikwit was the regional capital, but the country had collapsed after years of economic and political crisis. The city of dirt streets and wood huts with rusted metal roofs had reverted to small farms growing cassava, a starchy vegetable. Many old significant buildings were empty,” he said.

Ali S. Khan, M.D., M.P.H., dean of UNMC’s College of Public Health, was, at the time, a rising star in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He was 31 and already the epidemiology chief of the Special Pathogens Branch.

He had just returned from South America, where he worked with the hantavirus, a severe, sometimes fatal respiratory disease in humans transmitted by rodents. Suddenly, the disease detective was part of a four-man team assigned to control an even deadlier outbreak halfway around the world.

It was the same virus subtype that had broken out in 1976 in the northern part of the country, along the Ebola River, which gave the virus its name.

“I was honored to be given the opportunity to go in the first group. We wanted to understand why the virus reappeared after 20 years, challenge how it was transmitted and learn how to contain it.”

Enroute to, and in, Kikwit, the four medics quickly discovered that Ebola had captured the imagination of the press. Media teams outnumbered public health people at least seven to one.

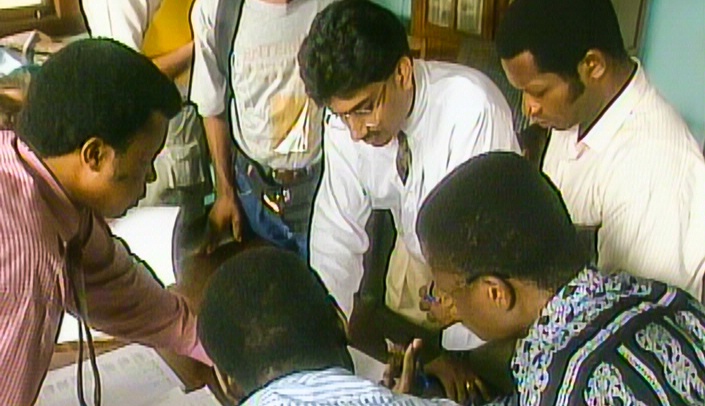

“It was embarrassing,” Dr. Khan said. Over the next two months the health care team grew to 30.

His first time in Africa, Dr. Khan’s job was to identify patient zero and attempt to determine the natural reservoir – from which the disease had come. He had one major drawback – he couldn’t speak French and would need an interpreter. Fortunately, two other teammates knew the language.

The hospital consisted of 10 separate pavilions with corrugated tin roofs connected by covered walkways.

“It was deserted. We found only one health care worker who was treating patients. The others had fled. People were lying on mattresses, no sheets, on metal beds. The living were among the dead. Vomit, diarrhea and blood covered the floors and walls. It was horrible.”

Dr. Khan worked 12- to 14-hour days tracking down who infected whom. He eventually identified patient zero, a farmer and brick maker who probably had been infected by a bat and passed it on to at least 20 family members and hospital workers.

“We identified every mechanism of transmission (body fluids) and set up procedures to stop the spread,” Dr. Khan said. Ebola occurs all the time in Africa, but it usually doesn’t infect more than one or two humans. The trouble is when it gets into the health care setting it becomes, what Dr. Khan was first to describe, a “super spreader” – infecting five or more people.

The virus was spread easily at the hospital with the constant reuse of needles to administer medicine for the ever present malaria.

“This was my first major outbreak of a virulent disease, and it was transformational. It defined the rest of my public health career – going from village to village, seeing people dying from malaria, and no one cares because it’s not Ebola.”

Malaria, an entirely preventable and treatable illness, caused an estimated 627,000 deaths in 2012, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. Closer to home, West Nile Virus, a fatal neurological disease in humans, is monitored annually in Nebraska, where 226 people were infected and five died of the disease last year.

Both are spread by mosquitos, the super spreader of the world. Two large wire sculptures of the insects decorate Dr. Khan’s office wall as a constant reminder of the danger in our own back yard.