It’s 1 o’clock in the afternoon on the first Thursday in October and there’s a delivery for research technologist James Askew in the Durham Research Center II.

He opens the FedEx envelope carefully. Inside are 10 screw-top tubes full of saliva. The specimen samples traveled all the way from Perth, Australia, where children between the ages of 4 and 6, with identified language impairments, spit into them. When there’s a big enough batch of samples to mail — about every two to three weeks — a collaborating researcher sends them on a two-day excursion to Omaha.

When Askew receives the samples, he places them on the countertop for tomorrow’s workload. Friday is DNA extraction day.

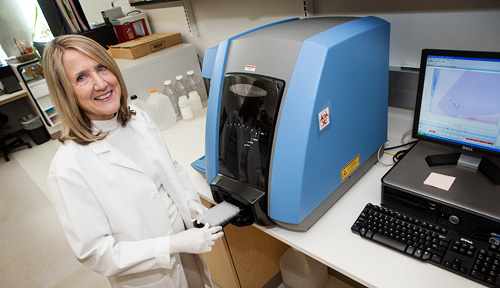

In the coming months, the lab staff, at the direction of Shelley Smith, Ph.D., director of developmental neuroscience at UNMC’s Munroe-Meyer Institute, will begin genotyping the DNA samples to test for “candidate genes” of language problems, such as stuttering, apraxia and speech delays.

So far, Dr. Smith’s lab has collected around 2,000 samples from Australia. They are currently sitting in a minus 20 degree Celsius freezer waiting for a ride on the “Bead Express” — a machine that will reveal more insight into what genes are responsible for language disorders.

“We hope to identify several genes that contribute to language impairments,” Dr. Smith said. “Those genes are likely to be part of a molecular pathway for development, and knowing the pathway can help us understand why it happens.”

Dr. Smith has studied the genetics of speech, language and reading disabilities for many years, but the Australian study is definitely her largest sample for language disorders, and the longitudinal nature of the study means that the process of language development can be tracked. After a recent five-year funding renewal from the National Institutes of Health, the goal is to collect around 5,000 saliva samples.

“The results of this study also could target how language disorders are diagnosed,” Dr. Smith said. “And there are certainly early intervention implications as well.”

The grant is actually through Mabel Rice, Ph.D., at the University of Kansas, who has been a collaborator and friend of Dr. Smith’s for more than 10 years. Dr. Smith points out that without Dr. Rice, the international collaboration would not be possible. Dr. Rice is quick to return the favor.

“Shelley has the respect of her international peers for her studies on the genetics of reading and reading impairment,” she said. “When I became interested in genetics etiology, I contacted Shelley. She is one of the best in her line of research.”