The University of Nebraska Medical Center has received a $1.2 million grant to participate in a five year clinical research study to compare the effectiveness of treatments for patients with catheter-associated staphylococcus infections – also called bloodstream infections or sepsis. The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is led by Duke University Medical Center and will involve 500 hospitalized patients at five medical centers in the United States and one in Europe.

The impetus for the study is antibiotic resistance is at an all-time high and development of new antibiotics is at an all-time low.

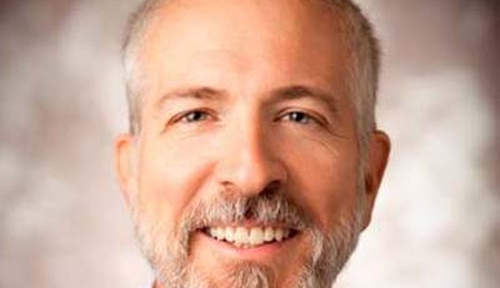

“Increasing antibiotic resistance and decreasing new drug discovery are like two trains speeding down the track toward a collision. When the collision occurs, we’ll have patients with infections due to resistant bacteria that we are not able to treat with any antibiotic,” said Mark Rupp, M.D., chief of the UNMC section of infectious diseases and medical director of The Nebraska Medical Center Department of Healthcare Epidemiology.

Staphylococci – also referred to as staph — are the most frequent cause of catheter-associated infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among the 80,000 patients acquiring infections due to catheters each year, about 8,000 to 10,000 die.

In the study, health professionals will use an algorithm — a treatment formula or clinical roadmap – to treat hospitalized patients with staph infections acquired through central venous catheters. It stipulates what tests to run, and depending on what species of staph the patient has, what treatment to use and for how long.

“This is an important project. We’re trying to figure out if we can use the algorithm to effectively treat patients and limit the unnecessary use of vancomycin, a leading antibiotic. We know some patients get vancomycin for longer than they need,” Dr. Rupp said. “We’re trying to figure out where that sweet middle ground is of treating patients with the right antibiotic for the right amount of time rather than under- or over-treating them.”

Central venous catheters are inserted in large central veins, such as in the arm, neck, leg, or under the collarbone. They enable health professionals to deliver drug treatment, hydration or sustenance for weeks or even months.

“Right now, treatment is left up to the judgment of the primary team seeing the patient,” said Dr. Rupp, principal investigator of the UNMC study and a member of the UNMC Center for Staphylococcal Research. “The algorithm, which was developed based on years of research and expert opinion, stipulates what tests to run and what should be in the decision-making process. We think this is a better way of driving the decision of the length of therapy.”

Staph infections generally stem from bacteria that thrive on human skin. The bacteria gain access to the bloodstream through the outer or inner surface of the catheter.

“That is why it is critically important to insert catheters using careful, sterile technique, then care for the catheters meticulously. It’s crucial to disinfect the catheter access port or hub each and every time the catheter is used to draw blood or administer medications,” Dr. Rupp said.

Through world-class research and patient care, UNMC generates breakthroughs that make life better for people throughout Nebraska and beyond. Its education programs train more health professionals than any other institution in the state. Learn more at unmc.edu.

JiWfLgbohf wdwP R