|

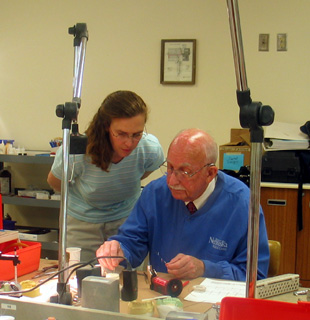

Kenneth Holland, D.D.S., shows third-year dental student Kelly Soder-Blackman how to solder wire to make a retainer. |

“It’s a beginning techniques course that teaches undergraduate third-year dental students how to use orthodontic materials,” explains Kenneth Holland Sr., D.D.S.

Dr. Holland is an associate professor at the dental school and the course director, a role he has kept for well over 50 years.

The UNMC College of Dentistry historically has been one of the very few dental programs to offer substantial courses in orthodontics to undergraduate students. Dr. Holland firmly believes that a more thorough orthodontic education is important for the general dentist.

“The more you know as an undergraduate student,” he said, “the more you will recognize potential orthodontic problems in your patients as a practicing dentist.”

|

Dr. Holland with some older tools of the trade, a gold retainer on a typo dont model, gold and platinum twin wire, stainless steel wire and a small vice to hold the wire while soldering. |

He first joined the College of Dentistry in 1950 at the request of Dr. Ludwick, then department chairman and a mentor of Dr. Holland’s. While he jumped at the opportunity to work alongside his former teacher, little did Dr. Holland know that this would lead to a life-long association with the dental school.

Dr. Ludwick asked Dr. Holland, who also maintained a private practice at the time, to teach a course in orthodontics once a week. “Instead of playing golf on my day off, I came over here every Wednesday,” chuckled Dr. Holland.

And he hasn’t left since.

|

Dr. Holland joined the department in 1950. |

“Well, I started off by burning my fingers,” she says smiling at Dr. Holland.

“Do you want me to show you?” asks Dr. Holland stepping closer to the table and picking up the soldering tool.

“Sure,” Soder-Blackman says getting up from her stool.

Dr. Holland sits down and repeats a scene that has occurred thousands of times over during the 54 years he has taught dental students the basic techniques of orthodontics.

“It’s important to show the students how to hold the wire, not just tell them,” Dr. Holland said later. “There is a certain way you position your hands so as not to get burned but still be able to properly solder wires together.”

It’s the kind of experience and wisdom that these students would get nowhere else.

“He shows us a lot of little tricks here in the lab,” Soder-Blackman said.

When Dr. Holland joined the department in 1950 there were only eight orthodontists practicing in Nebraska. Of those, only two practiced outside of Lincoln and Omaha.

“In those days I had patients who drove from Valentine and Chadron to Lincoln to see me,” Dr. Holland said.

Dr. Holland became convinced that a rural state like Nebraska needs general dentists in remote areas with orthodontic knowledge and skills. Those dentists would be better able to treat minor cases, as well as recognize more complex cases and refer them to an orthodontist.

|

Dr. Holland watches as Jeffrey Nickel, Ph.D., seated, explains proper soldering technique to third-year dental students Mollie McNamara, far left, and Brian Ozenbaugh, far right. |

“Ken’s the one that’s been here through it all,” said Peter Spalding, D.D.S., and current department chairman. “He’s been the stabilizing force through some challenging transitions.”

In the 1950s there were very few training programs for orthodontics, Dr. Spalding said. Students took a specialized course at one of a very few schools in the country or trained under another orthodontist, as Dr. Holland did.

In 1952, two years after he started teaching, Dr. Ludwig died, leaving Dr. Holland as the only orthodontist on staff, Dr. Spalding said. Today there are nine full-time and part-time instructors.

“The success of this program has largely been due to the dedication of Dr. Holland over the years,” he said.

A lot has changed in orthodontic dentistry as well, Dr. Holland said. For example, at one time the bands used in braces were made out of platinum and the wires out of 18k gold until the introduction of stainless steel in the 1950s, which made them more affordable.

And it was a Nebraska dental student, who raised cattle in the Sand Hills that came up with the idea of making stainless steel crowns for the animals to protect their teeth from wearing down because of eating hay with sand in it.

After the student asked Dr. Holland if it would be possible to make crowns for cattle, he contacted an orthodontic supply company to do just that and the College of Dentistry received considerable publicity for the innovation.

Another momentous change, he said, occurred in the early 1940s when extraction of the bicuspids to make room for alignment of teeth became acceptable in the profession.

“The focus of dentistry for so long had been on preserving all the teeth,” said Dr. Holland. “That when a patient needed his teeth straightened we expanded the dental arches to make room for the crowded teeth.”

But once the patient quit wearing the retainers, the arches often collapsed, becoming crowded again. Research demonstrated that extraction of teeth sometimes was necessary to maintain the individual patient’s arch form.

Richard Bradley, D.D.S, remembers Dr. Holland as a very patient, very kind and meticulous instructor. “He was very thorough and taught us how to manage patients very nicely,” said Dr. Bradley, a former student who later became dean and now is a part-time instructor at the College of Dentistry, teaching periodontics on Mondays. “Every once in a while I go down to the lab and watch him, and he is right there with the students like he was 30 years ago.”

“I’ve always had a lot of respect for Dr. Holland,” said Sam Weinstein, D.D.S., who is now retired and living in Arizona. Dr. Weinstein started the college’s graduate program in orthodontics in 1955.

When Dr. Weinstein came to the dental school he found a friend and ally in Dr. Holland.

“He has contributed a great deal to the graduate and undergraduate programs,” Dr. Weinstein said. “He is a very sincere and very hard working person.”