|

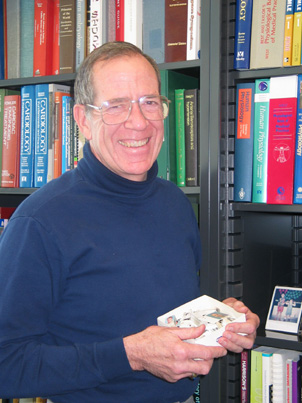

Kurtis Cornish, Ph.D., with some of the flashcards he’s studied over the years to learn student’s names and faces. |

The UNMC associate professor of physiology and biophysics is known for knowing the names of his students, all 120 or so, when they walk into his Function of the Human Body course each January.

For Dr. Cornish, that means studying their faces and memorizing their names from composites cut into postage-stamp sized flashcards, which he carries everywhere in his pocket from September to January.

“Initially I did it to get them actively involved in the lecture,” Dr. Cornish said from his fifth floor office in the Durham Research Center. “Later, I learned the real payoff was in getting to know who they were.”

A consummate educator, Dr. Cornish is one of four UNMC faculty members to be honored with the 2004 Outstanding Teacher Award from the UNMC Faculty Senate. The awards will be given at the Annual Faculty Meeting on Tuesday, April 20, at 4 p.m. in the Suzanne & Walter Scott Auditorium in the Durham Research Center.

“I love to teach and love to work with the students,” he said. “It’s what makes my job worthwhile.”

|

Kurtis Cornish, Ph.D., helps scientists prepare animals for research. |

Dr. Cornish also coordinates the annual “June” term, a three-day session that allows third-year students to perform basic medical procedures they’ll need in their clinical rotations. It’s not unusual to see students performing naso-gastric tube placements on Dr. Cornish.

A champion of the problem-based learning approach to medical instruction, Dr. Cornish also coordinates a basic science elective for fourth-year students. In addition, he’s a familiar face at Match Day, where he videotapes students as they reveal their resident destinations; the annual hooding ceremony, where he has served as a “reader;” white coat ceremony and graduation. He even helps coordinate the celebration party for first-year students after their comprehensive final.

A native of Salt Lake City, Dr. Cornish came to UNMC in 1977 as a post doc in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics. After his two-year stint, he turned down a job in Indiana, when UNMC’s Joseph Gilmore, PhD., said someone with surgical abilities was needed to work with chronically instrumented animals. As a UNMC faculty member, Dr. Cornish was thrust into the new role of teacher. “I initially got horrible evaluations,” from pharmacy and physical therapy students, he said.

By 1980, the U.S. Army nurse in Vietnam had found his passion – teaching UNMC medical students. “I understood what the medical students needed to know,” said Dr. Cornish, who worked as a nurse in a hospital while earning his master’s degree at Brigham Young University and his Ph.D. degree at Wake Forest University.

Today, Dr. Cornish is consistently rated among the top 5 percent of faculty who teach in the basic science years. He has received three Golden Apple Awards and the student-initiated Alvin Earle Outstanding Health Science Educator Award. He also was one of two recipients of the initial Hirschmann Golden Apple Award, a prestigious honor awarded by senior medical students to the basic scientist who had the most influence on them through four years of curriculum.

“A good teacher can demand a lot, but also has to be willing to pay the price to help them meet the standards,” Dr. Cornish said.

It’s clear he goes the extra mile to help students. A self-proclaimed maverick, Dr. Cornish says multiple-choice exams “train students to recognize, but not to think.” Instead, he gives written, essay exams, which require 40-plus hours to grade. “It’s more demanding and asks them to learn at a higher level,” he said.

Dr. Cornish realizes the material he teaches is valuable, but says, “it’s also critical for medical students to remember they need to treat people. I try to teach that as well, even though it’s not a class or core.”

In addition to teaching, Dr. Cornish does surgical procedures for a number of different investigators who use animals in their research.

He and his wife Lorraine have seven children scattered from Lincoln to Virginia to New York. He is active in his church, spent years as a Scout leader and, when he’s not climbing stairs in the Durham Research Center, enjoys backpacking with his sons.

Meanwhile, the flashcards he studies are always close at hand. “If I see an M4 in the hallway they still expect me to know who they are,” he said, as he reviewed old flashcards of second-, third- and fourth-year students.