|

Pete Iwen, Ph.D., left, and Paul Fey, Ph.D., are part of a team of researchers whose goal it is to become experts in the bacteria known as Francisella tularensis. |

The project is supported by the University of Nebraska and Tobacco Settlement Funds through a program initiated by Tom Rosenquist, Ph.D., UNMC vice chancellor for research, and Prem Paul, Ph.D., UNL vice chancellor for research and dean of graduate studies.

UNMC began the work in the past couple of months as part of a continued plan to expand infectious disease research and build academic and research centers of excellence.

Studying strains

Researchers at UNMC, in collaboration with scientists at UNL, are gathering information on the genetic makeup of the organism by performing tests to define the differences in multiple strains of F. tularensis. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has approved UNMC as a repository for bacteria such as Francisella tularensis.

|

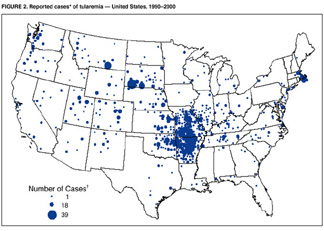

Map showing cases of tularemia within the U.S. over a 10-year period (1990-2000). The dots represent the number of cases reported: the smallest dot represents 1 case; medium-sized dot, 18; and large dot, 39. |

“This is a unique opportunity for scientists and academicians to study this important organism, and we hope our research will be an academic exercise that contributes to the prevention of an attack,” Dr. Fey said.

A potential threat

F. Tularensis recently was classified by the U.S. government as a Category A agent, which has the greatest potential for causing harm if used in a bioterrorist attack. It can be dispersed in the air through aerosolization and inhaled in the lungs, similar to how bacillus anthracis (the bacterium that causes anthrax) and the smallpox virus can be used, researchers say.

“This agent poses a high potential threat for use in bioterrorism and a risk to national security,” said Pete Iwen, Ph.D., UNMC assistant professor of pathology and microbiology. “There’s no good vaccine available for public use. In the past, it had limited use in the protection of lab workers and military personnel, but the FDA is reevaluating the vaccine because of problems associated with it.”

|

Francisella tularensis grown on culture medium after five days incubation. |

Tularemia, also known as “rabbit fever,” is caused by a natural occurring bacterium found typically in wild animals, especially rodents, rabbits and hares, and occasionally in pets such as cats, according to the CDC.

People come in contact with F. tularensis in a variety of ways — the bite of an infected insect, usually a tick or deerfly; handling infected animal carcasses; eating or drinking contaminated food or water; or breathing the bacteria.

About 200 cases of tularemia, including three to four in Nebraska, are diagnosed annually, Dr. Fey said.

“The death rate can be 40 to 60 percent if inhaled,” he said. “Right now, there’s not a great deal known about how the organism causes disease.”

In the United States, tularemia is almost always a rural disease, reports the CDC. It is not known to be spread from person to person. People who have been exposed should be treated as soon as possible with antibiotics.

Symptoms of the disease

|

Paul Fey, Ph.D., prepares for work in the laboratory. |

Goal: to develop an antigen

Drs. Fey and Iwen and their colleagues are conducting basic research to learn more about the genetic makeup of F. tularensis to understand what genes or proteins in the organism cause the disease and ultimately develop an antigen — a vaccine — for protection against the organism.

“We hope that our experience working with F. tularensis and other similar agents will enable us to expand our knowledge base and receive more funding,” Dr. Fey said.

Dr. Iwen: “An opportunity”

|

Gram stain of wound aspirate showing the small gram-negative rods characteristic of Francisella tularensis. |

Team submits grant

UNMC and UNL researchers have applied for a $26 million grant to the U.S. Institutes of Health, with the ultimate goal of finding a new vaccine to prevent tularemia. The 4-inch-thick grant proposal names Steven Hinrichs, M.D., as the principal investigator, along with 29 researchers representing UNMC and UNL, Kansas State University, University of Missouri-Columbia, University of Iowa, University of Kansas, Iowa State University, Viraquest, Inc. of North Liberty, Iowa, and Midwest Research Institute in Kansas City, Kan. Other UNMC researchers include Tom Jerrells, Ph.D., and Rakesh Singh, Ph.D., from the department of pathology and microbiology.