Here is what Pulitizer Prize-winning American historian Bruce Catton, writing in American Heritage magazine, had to say about “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave Written by Himself.”

“Douglass did not know much about himself. Rather vaguely, he was aware that he had been born somewhere around 1817; he had seen his mother ‘to know her as such’ no more than four or five times in his life, usually very briefly and at night, and he grew up knowing nothing better than the life of the stalled ox or the mule, a wholly owned creature with no rights than anyone was bound to respect.

“More than one hundred years later, this account of the things men can do to those who are completely in their power is something to make the blood turn cold. If there was a kindly, humane side to chattel slavery, this man who lived far outside of the cotton belt, who was for long periods a trusted house servant, who was even hired out (by his owner) to work in a shipyard, far from the eye of the man with the whip — this man, who should have seen that humane side if any slave could see it, never got a glimpse of it. ‘But for the hope of being free,’ Douglass wrote, ‘I have no doubt but that I should have killed myself.”

Who today can imagine, let alone question, the long-term trauma and disorders that might infuse a child taken from his mother at 12-months old and never allowed to see her again, or know his own date of birth? How could such acts become normal business procedures for millions of people, without some deeply rooted side effects in the social fabric of the nation?

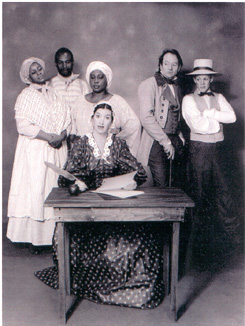

Don’t just take Frederick Douglass’ word for it. See “Let My People Go: Trials of Bondage in Words of Master and Slave” Friday at 11:30 a.m. in the College of Nursing’s Cooper Auditorium and experience reenactments of astounding case histories from the slave era and post-Civil War South. Remember, each vignette is base upon documented history.