|

Randy Toothaker, D.D.S., center, holds an articulator, which allows a restorative dentist to study a patient’s replicated jaw movements in order to accurately design and fabricate a prostheses upon dental implants. To his left is post-graduate prosthodontics student Yannis Soultanis, D.D.S. To his right is dental assistant Kathy Givens. |

Cultural traditions evolve over time. While some fade away unnoticed, others leave permanent marks that won’t go away without intervention.

Such is the case for some Sudanese refugees. What once was a revered tribal ritual of removing teeth in the Sudan is now seen as undesirable. In the Sudan, missing lower, front teeth was seen as a sign of becoming an adult.

But now, many of the Sudanese who spent years in refugee camps after fleeing their war-torn country want to look, speak and be able to eat foods like their fellow Americans. They would like to get back the four to six teeth they once had forcibly removed as children.

They say their missing teeth create social, language and dietary barriers, and people who don’t understand the Sudan ritual look at them funny and ask questions.

Two faculty members from the UNMC College of Dentistry and University of Nebraska-Lincoln, with the help of corporate sponsors and countless others, are currently restoring the lost teeth of five Sudanese refugees in Lincoln.

Humanitarian, educational opportunity

Mary Willis, Ph.D., assistant professor, UNL department of anthropology and geography, contacted Randy Toothaker, D.D.S., UNMC College of Dentistry, months ago to see if it would be possible to help some of the Sudanese with whom she works.

|

Dental residents Kyle Smith, D.D.S., Bryan Cochran, D.D.S. and Matt Byarlay, D.D.S., prepare David Apiu for oral surgery. |

“My first thought, besides the humanitarian aspect, was the educational opportunity for our students,” said Dr. Toothaker, associate professor and director of the postgraduate prosthodontics program. “We are always looking for ways to increase exposure to clinical implant opportunities.”

From an oral health perspective, Dr. Toothaker said, the dental implants will make it possible to eat traditional American foods, but also could prevent serious future oral health problems, as well as prevent excessive back tooth wear and bone loss. He said it also would provide insight from a dental education perspective in understanding oral health in diverse and underserved populations.

Outreach efforts benefit many

Dr. Toothaker also looks at the opportunity as one of community outreach, providing care to those who may not otherwise get it.

“We didn’t go out to these patients and convince them to let us provide this therapy,” Dr. Toothaker said. “Dental implant therapy is costly. One of the reasons we are able to do this is because we had some companies step forward and offer to help in this unique cultural situation and very specific clinical situation.

“The information and experience that can be gained by future clinical and scientific questions from the treatment of these types of cases will be of benefit to all Nebraskans.”

He said he also was moved by the survival stories of the Sudanese refugees.

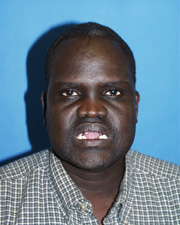

|

Dobueny Bukjiok shows his smile minus several missing bottom teeth that were removed in childhood. |

“Many of them took off running to save their lives in the war-torn country,” Dr. Toothaker said. “Some were in refugee camps for nine years. Literally, you had boys carrying boys across crocodile-invested rivers while these predators attacked someone nearby them. Some remember calling for their absent mothers as they were running across the desert.

“These people have been through tremendous strife.”

Getting dental implants

The five Sudanese undergoing oral surgery to receive dental implants first have their jaws measured to create a prosthesis. Titanium implants, shaped like dental roots, then are placed in the bone four to six months after the patient’s jawbone has firmly attached around the implant.

Once the gums around a post – which connect the implant to the replacement teeth — are healed, the artificial teeth are fitted onto the posts.

A cultural transformation

The surgical transformation, in a sense, provides a cultural transformation. But the Sudanese, representing the Dinka, Nuer and Maban tribes, don’t see it as turning their backs on cultural traditions.

“Culture isn’t just identifying people with marks or missing teeth,” said Dobuony Bukjiok, 40, of Lincoln, “It’s everything a culture does on a day-to-day basis. We’re still Sudanese but with an improved image. Even our fathers and grandfathers cannot say why these things were done.”

“In our own culture, we didn’t mind,” said David Ajang Ajak, a Sudanese man living in Lincoln. “Now, in America, everybody has teeth. We look ugly among the people. Now that we are here, we regret that we had our teeth removed. If I have children, they will never take out their teeth.”

Ajak said his parents now look at his desire to have all his teeth as a sign of an educated person, one who is grown up. “They think it’s OK. They are envious.”

Remembering the ritual

Each of them remembers being scared and feeling the pain of having the teeth or tooth buds removed during a ceremony around the age of seven to 10 years old. They weren’t told why it was done. Some thought removing the teeth would prevent diarrhea.

Because it was undesirable to cry during the procedure, in which they used fishing knives to remove the teeth, girls went first. Tribesmen told the boys that if the girls didn’t cry, then the boys couldn’t cry either, said Santino Deng, a Sudanese refugee and Lincolnite.

“You were happy if you endured the pain,” Ajak said. “People would consider you were a man.”

Several years ago, the Sudanese government began dissuading tribes from removing teeth for health reasons, but some tribes still engage in the practice.

Many of the Lincoln men are adamant that if they go back to visit their country, they will do everything they can to educate tribesmen why they shouldn’t remove teeth.

“People die from this practice,” said Duol Rut, who explained how people have bled to death because they had hemophilia. Rut is a refugee who also lives in Lincoln.

Who is involved?

Dr. Toothaker and Dr. Willis are seeking additional support through grants and donations. About 18 people are involved in the project, including residents in the UNMC College of Dentistry’s prosthodontic and periodontic specialty programs, dental assistants, faculty and staff.

“I like the experience,” said Kyle Smith, D.D.S., a periodontics resident. “Their situation is phenomenal. I like being able to help out.”

Implants are being made possible with donations for surgical and restorative components from Nobel Biocare, USA of California, and laboratory services and materials from Dental Designs, Inc., of Lincoln.

The college has donated the faculty and resident time for the educational benefits that are being provided to the students. Dr. Toothaker said he will be applying for grants to study the feasibility and benefits of providing definitive restorations even sooner to patients after the initial implant surgery — even the same day or week.

“We have found a very unique situation right in front of us where patients, with literally the exact same clinical findings, are able to be treated with implants with minimal to no preparatory dental work required. It’s a win-win situation for the patients, faculty and students involved and the educational benefits are both immediate and long-term.”