While Al Stammers was in junior high school, he told his mother he hoped to be a teacher one day. His mother, a homemaker with no advanced education, warned him to always be careful as an educator and understand the power he would have as a teacher – to never neglect his responsibility to do the very best for all of his students.

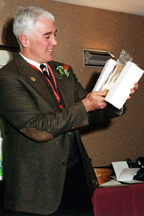

As Mary Haven, associate dean of the School of Allied Health Professions, noted at Stammers’ going away reception on Jan. 10, there is no overstating how deeply Stammers took his mother’s message to heart during 10 years as director of SAHP division of clinical perfusion education.

“It is not often that it can be said that one person is responsible for the accomplishments of an entire program,” Haven said. “But in this case, we can say that. Al took a program in its infancy and made it the top program in the nation. He found space for a student study area, space for a secretary and a building for the laboratory work – and we all know how hard it is to find space on this campus.

“Al developed the curriculum which provided students with the background to score 30 to 40 points higher than the national average of their peers on national board exams. In fact, 100 percent of Al’s students passed these exams on their first attempt, versus a national pass rate of 60 to 70 percent.

“Al cajoled industrial sources to donate equipment for teaching and funds and instrumentation for conducting research. Not only did he help his students with research projects, but he insisted students rehearse their presentations until they were flawless. Al’s students have won national and international awards for their presentations and now do rotations as far away as London, England.

“And Al did all of this while earning personal awards for outstanding research, teaching and contributions to clinical perfusion education. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, without question, this is one of Al Stammers’ finest decades.”

When Stammers came to UNMC, the program had been in existence for about a year and had graduated one class. “My administrative equipment was a typewriter and one drawer in a filing cabinet located in the thoracic surgery office,” he said. “I didn’t even have a desk. There wasn’t a single computer for our department.

When Stammers came to UNMC, the program had been in existence for about a year and had graduated one class. “My administrative equipment was a typewriter and one drawer in a filing cabinet located in the thoracic surgery office,” he said. “I didn’t even have a desk. There wasn’t a single computer for our department.

“But in the early 90s, I was on faculty at the Medical University of South Carolina and there were only two positions as director open in the country – in Des Moines, Iowa, and at UNMC. I always knew I wanted to be an educator. I was offered both positions, but my wife liked Omaha better. I really can’t say that it was the med center that sold me, initially, as much as our feeling that Omaha was a much better place to live.”

Stammers has great pride in how far the program has come in its research capabilities. In the beginning, there was virtually no research being done in clinical perfusion education at UNMC. Since 1992, the division has presented at least 85 papers, written four or five chapters in perfusion textbooks and conducted the largest annual meeting for perfusionists for several years. In addition, the division sponsors its professional association’s annual regional conference.

Stammers stumbled into clinical perfusion as a vocation. He was a research assistant in a lab in Syracuse, N.Y., and there was a perfusionist who used to stop by his lab. They became friends and the more he listened to her, the more interested he became in perfusion science. At that time in the early 1980s, perfusion science was an unglamorous profession known for long hours, low pay and limited responsibility. But the great increase of cardiac surgery at the end of the decade led to a tripling in perfusionists’ salaries and new interest in the profession throughout the United States.

Stammers’ friend ended up being his perfusion program director and mentor. Most importantly, she instilled into him the need to do research, especially since most perfusionists at that time were clinicians who did no research at all.

“Research is what built our program here, paid all our bills and put UNMC on the map with perfusion scientists worldwide,” Stammers said. “We’ve had visiting scholars from China who spent up to a year with us. We continue to get applications from perfusion scientists from Asia and Europe who want to train here because of the education and research we do.”

The transition team will strive to maintain the standards of perfusion excellence left by Stammers, Haven said. Dr. John Tinker, the chair of the department of anesthesiology, will remain as medical director of the perfusion program. Dr. Reba Benschoter, former associate dean of SAHP and the person who worked with Stammers in setting up the curriculum, will be the interim program director. Mark Moreno, a clinical perfusionist with NHS, will be the clinic coordinator.

Stammers is taking off his educator’s hat and becoming a full-time clinician in Pennsylvania. His move will enable him to pursue more advanced facilities and treatment opportunities for his autistic son. Meanwhile, he’ll keep Cornhusker time with an engraved mantel clock presented by his students, and remember the Nebraska prairie with a panoramic photo print, also a gift.

Perhaps, the best farewell present Stammers received was from Ben Greenfield, a first-year perfusion student. Singing acapella to Simon and Garfunkle’s classic hit, “Mrs. Robinson,” Greenfield’s creative version refrained, “Here’s to you, Al Stammers, we’ll miss you more than you will ever know.”