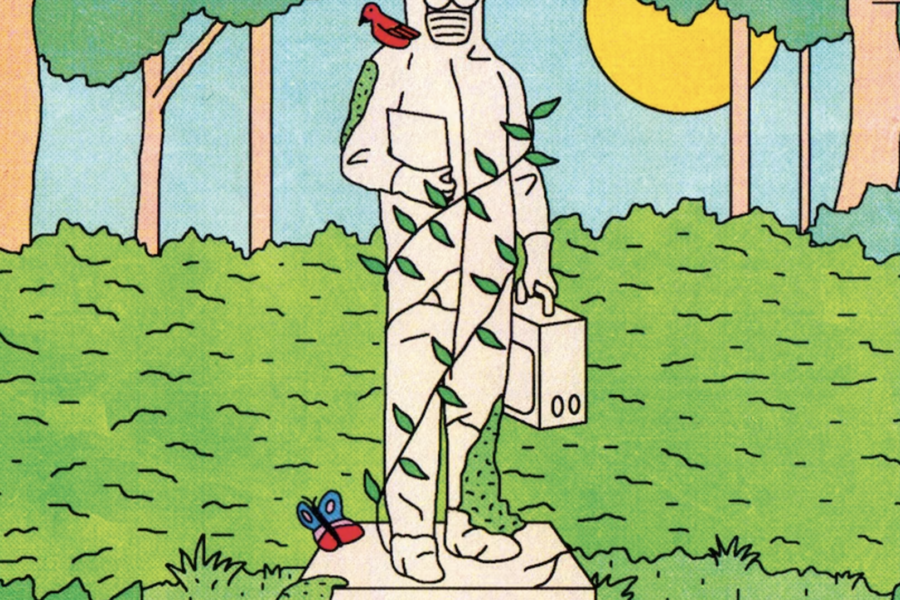

Washington Post Because of information overload and the monotony of pandemic life, your brain may already be forgetting parts of the covid years.

How much do you remember about the past three years of pandemic life? How much have you already forgotten?

A lot has happened since the “Before Times.” Canceled proms, toilet paper shortages, nightly applause for health workers, new vaccines, waitlists for getting the first jab, and more.

Covid disrupted everyone’s lives, but it was truly life-changing for only a sizable subset of people: those who lost someone to covid, health-care workers, the immunocompromised or those who developed long covid, among others.

For the rest of us, over time, many details will probably fade because of the quirks and limitations of how much our brains can remember.

“Our memory is designed not to be computer-like,” said William Hirst, professor of psychology at the New School for Social Research in New York. “It fades.”

Why we might forget a pandemic

Forgetting is inextricably intertwined with memory.

“A basic assumption that we can make is that everybody forgets everything all the time,” said Norman Brown, cognitive psychology professor researching autobiographical memory at the University of Alberta. “The default is forgetting.”

To understand why we may forget parts of pandemic life, it helps to understand how we hold on to memories in the first place. Your brain has at least three interrelated phases for memory: encoding, consolidation and retrieval of information.

When we encounter new information, our brains encode it with changes in neurons in the hippocampus, an important memory center, as well as other areas, such as the amygdala for emotional memories. These neurons embody a physical memory trace, known as an engram.

Much of this information is lost unless it is stored during memory consolidation, which often happens during sleep, making the memories more stable and long-term. The hippocampus essentially “replays” the memory,which is alsoredistributed to neurons in the cortex for longer-term storage. One theory is that the hippocampus stores an index of where these cortical memory neurons are for retrieval — like Google search.

Finally, during memory retrieval, thememory trace neurons in the hippocampus and cortex are reactivated.

Notably, memories are not fixed and permanent. The memory is subject to change each time we access and reconsolidate it.

What we remember tends to be distinctive, emotionally loaded and deemed worthy of processing and reflecting upon in our heads after the event happened. Our memories are centered on our life stories and what affected us personally the most.

Against this neural backdrop, the pandemic would seem unforgettable. It was a frightening, historic event, the likes of which most people have never encountered before.

Information overload and monotony interfere with memory

Butso much has happened, it was difficult for our brainsto encode the overload of information we had to sift through — masks, social distancing, superspreaders, more cases, more deaths, new waves and new variants such as omicron and delta, and who even remembers all the subvariants?

“This is a very fundamental memory phenomenon,” said Suparna Rajaram, psychology professor who researches the social transmission of memory at Stony Brook University. “Even for such salient emotional events and salient life-threatening events, that the more you have of it, the more you will have trouble capturing all of them.”

Even Rajaram, who is conducting pandemic-related memory research, said she and her colleagues have difficulty recalling some of the events they are asking their participants about.

New memories, which happen by simply living more life, interfere with memories ofolder events. New events are more salient and easier to remember because we are more likely to talk about them and “rehearse” them,by repeatedly remembering and reconsolidating them. Stress, something the pandemic produced in abundance, also interferes with the creation of new memories.

In addition to information overload, the pandemic was monotonous for many people stuck at home. “It was very much the same and the same thing over and over again,” said Dorthe Berntsen, professor of psychology specializing in autobiographical memory at Aarhus University.

When events are uniform, they are harder to recall. “The memory sort of puts it together as almost one event,” she said. “So therefore, I think we will have quite unclear memories from those specific years.”