Enough pints of beer can have you falling off your bar stool or loudly reciting lyrics to early 2000s jams to total strangers, because alcohol can get past one of the strongest defenses in the body. If you’ve ever been drunk, high or drowsy from allergy medication, you’ve experienced what happens when some molecules defeat the defense system called the blood-brain barrier and make it into the brain.

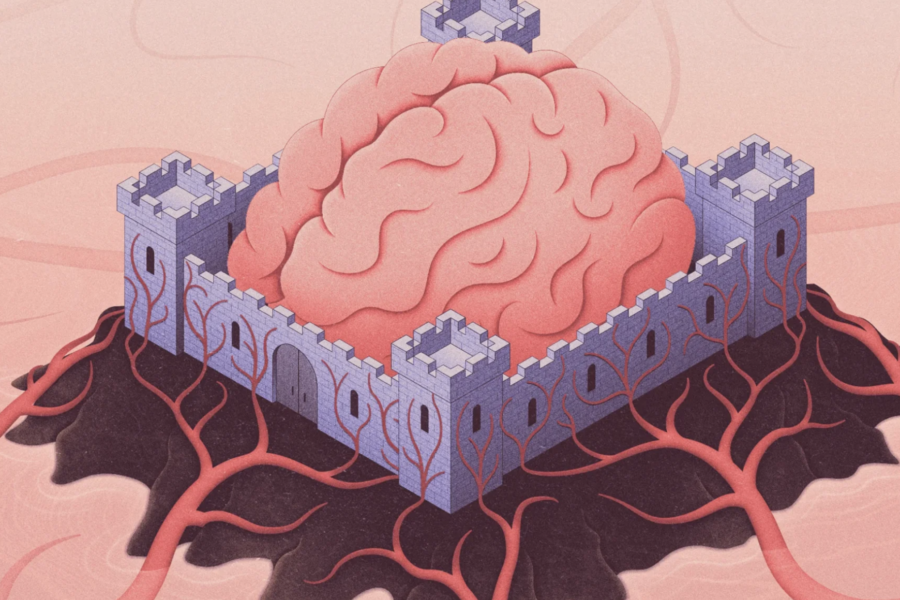

Embedded in the walls of the hundreds of miles of capillaries that wind through the brain, the barrier keeps most molecules in the blood from ever reaching sensitive neurons. Much as the skull protects the brain from external physical threats, the blood-brain barrier protects it from chemical and pathogenic ones.

While it’s a fantastic feat of evolution, the barrier is very much a nuisance for drug developers, who have spent decades trying to selectively overcome it to deliver therapeutics to the brain. Biomedical researchers want to understand the barrier better because its failures seem to be the key to some diseases and because manipulating the barrier could help improve the treatment of certain conditions.

“We’ve learned a lot over the last decade,” said Elizabeth Rhea, a research biologist at the University of Washington Medicine Memory and Brain Wellness Center. But “we’re definitely still facing challenges in getting substrates and therapeutics across.”

Protection, but Not a Fortress

Like the rest of the body, the brain needs circulating blood to deliver essential nutrients and oxygen and to carry away waste. But blood chemistry constantly fluctuates, and brain tissue is extremely sensitive to its chemical environment. Neurons rely on precise releases of ions to communicate — if ions could flow freely out of the blood, that precision would be lost. Other types of biologically active molecules can also twang the delicate neurons, interfering with thoughts, memories and behaviors.

“It’s really there to control the environment for proper brain function,” said Richard Daneman, an associate professor of pharmacology at the University of California, San Diego.