Why Nebraska?

Vision and an All-Star, All-Volunteer Team

How did Omaha, Nebraska, an ambitious, but decidedly mid-sized Midwestern city, become a global epicenter for biopreparedness? It started with a vision. And, with people. Years before Ebola became a worldwide buzzword, the state’s academic medical center, UNMC, primary clinical partner Nebraska Medicine, and the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, came together to create the Nebraska Biocontainment Unit. One of only a select handful of such specialized units nationwide.

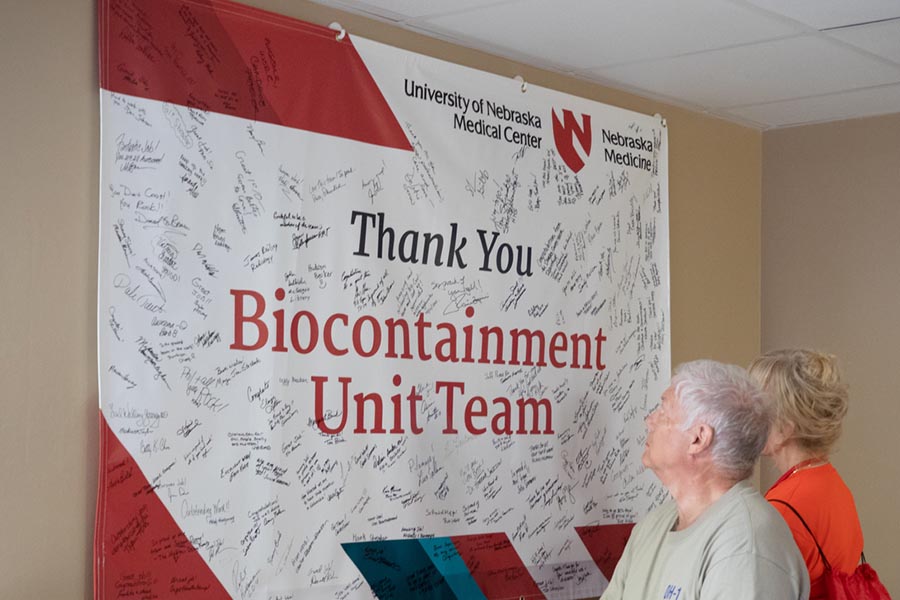

But without people, that’s merely expensive infrastructure. Nebraska’s difference is an all-star, all-volunteer team that dedicated itself to being ready for a crisis it did not yet know, at some future date that had not yet come. Years went by. Nearly a decade. Save for a few false alarms, the unit sat empty. The team, driven by a vision, kept on.

“By the end of that nine years,” longtime Nebraska Biocontainment Unit medical director Dr. Phil Smith told Nebraska Educational Television, in an award-winning documentary, “we had the hard-core biocontainment geeks, if you want to put it that way.”

They were firefighters, forever drilling. But their call never came. Some openly wondered, Would it ever? Dr. Smith felt the rumbling: “I know there were times when the hospital was full, we had to divert people to other hospitals. They were saying, Why are we just letting this 10-bed unit sit there?” But the vision held.

“Dr. Smith put his foot down about a hundred times,” said Dr. Daniel Johnson, who would later join the unit: " 'We need to keep this unit. We are going to need it. Trust me.’ ” In Omaha, Nebraska, leadership agreed.

“To their credit,” Dr. Smith said, “they had the long vision. They could see the global trends. And the fact this was something that could be very useful if there were an outbreak down the line.”

Ebola

In 2014, Ebola, one of the world’s deadliest special pathogens, was ravaging West Africa like a wildfire.The State Department called. American medical missionaries had become infected. Was the Nebraska Biocontainment Unit ready? Always ready. And with that, an Ebola patient was in the air and on his way. To Nebraska.

“I tingled from head to foot,” Dr. Smith said.

“We’d trained 10 years for this moment. And these are our fellow Americans. And if we weren't going to seize this, then everything that we have done has been for naught.”

Shelly Schwedhelm

Executive Director, Emergency Management and Clinical Operations

“Dr. Smith and Shelly had told us that everything was going to be good,” said nurse Betsy Flood, “we had prepared for this. We knew what we were doing. And they had this kind of calm, that, it was like, Well, they say it’s going to be OK. It’ll be good. We know what we are doing. We’re smart. We’ve practiced. Let’s go.”

They did what first responders always do: They strode calmly and deliberately toward the crisis, not away from it. The lessons learned were invaluable. Other aspects of the medical center became involved. Global partnerships were established. Papers were written. Nebraska protocols declared good as gold.

In Dallas, two nurses who hadn't had this specialized training became infected with Ebola (they were treated and cured). But in Omaha, the team conducted its work without incident, with flying colors. The Nebraska Biocontainment Unit team was lauded with international headlines, earned praise from President Barack Obama.

A mid-sized Midwestern city had become a global epicenter for biopreparedness. The team members seemed to echo a common theme: Yes, there was that element of adrenaline. You might even call it fear. But once they saw the patient in person it all melted away. What they saw was someone who needed care. And that’s what they do. That’s why they drill. That’s how the vision held strong for all those years. As the first patient with Ebola rode in an ambulance on the way to the Nebraska Biocontainment Unit, Kate Boulter, a nurse, looked down into his eyes. She told him the team was ready. That he would receive the best care.

He was grateful. “Welcome to Nebraska,” she said.

In the spring of 2020, COVID-19 quickly took over news headlines across the world.

As with during the Ebola crisis, the Global Center for Health Security, UNMC, and Nebraska Medicine were once again called upon by the U.S. government for critical assistance.

In February 2020, leveraging the state-of-the-art National Quarantine Unit (the nation’s only federally funded quarantine facility) and the Nebraska Biocontainment Unit (the largest of its kind in the U.S.), 57 Americans evacuated from Wuhan, China, and 13 passengers from the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan were safely transported to Nebraska for care and monitoring.

Since then, the Global Center and UNMC’s College of Public Health have collaborated to develop specialized training and resources to address the COVID-19 global pandemic.

UNMC and Nebraska Medicine and the Global Center for Health Security have worked hard to lead during the COVID-19 pandemic in treatment, training and quarantine methods.